Arizona Historymakers Interview

Arizona Historymakers ™

Oral History Transcript Historical League, Inc. © 2018

Historymakers is a registered trademark of Historical League, Inc.

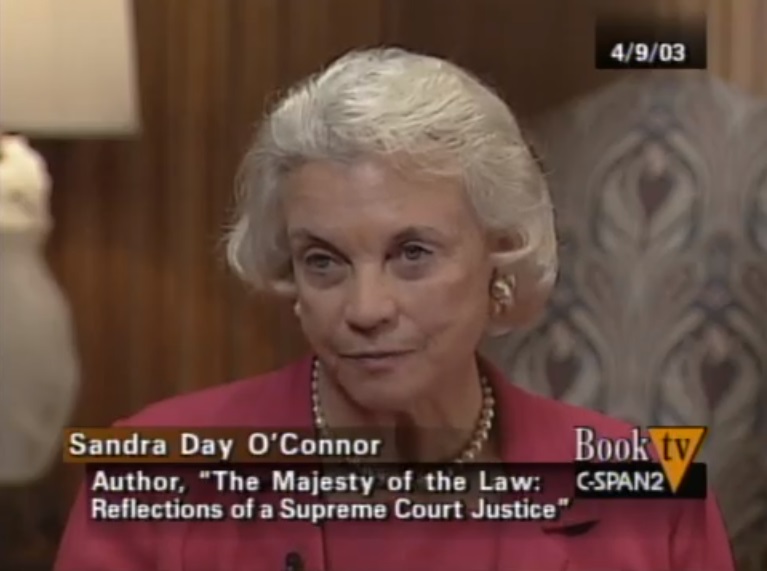

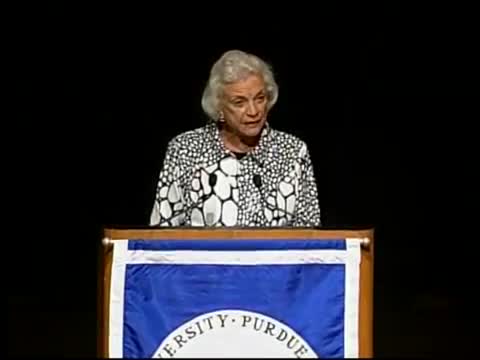

SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR

1930

Honored as a Historymaker 1992

First Woman Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

The following is an oral history interview with Sandra Day O’Connor (SO) conducted by Harriett Haskell (HH) for Historical League, Inc. on January 31, 1980 in the Capitol Building of the Court of Appeals, Phoenix, Arizona.

Transcripts for website edited by members of Historical League, Inc.

Original tapes are in the collection of the Arizona Heritage Center Archives, an Historical Society Museum, Tempe, Arizona.

HH: Judge O’Connor, where were you born?

SO: I was born in El Paso, Texas, but that wasn’t really home. I…my parents lived and still live on a ranch in Eastern Arizona. But it’s in a very remote part of the state…it’s in Greenlee County, and there was no hospital nearby and my mother’s mother lived in El Paso, so when it came time for me to born, she made the trip to El Paso a few days ahead and I was born in El Paso in Hotel Dieu.

HH: Your father’s a rancher, then? Or was?

SO: Yes, yes, still is and the ranch is actually in…half in Arizona and half in New Mexico. The house is in Arizona, but to reach the house you have to drive a good many mile through New Mexico. But we are legally Arizona residents, and of course, after my birth, we immediately returned back to the ranch where I grew up. The ranch is the Lazy B Cattle Company