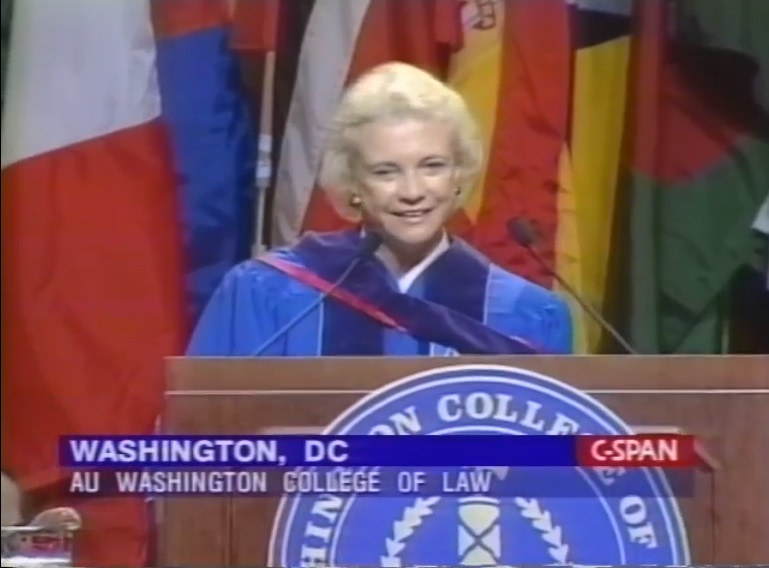

President Ladner and Dean Grossman, and faculty graduates and friends of Washington School of Law. What a special day. This is for all of you graduates of the American universities, Washington College of Law, and for your families who helped you to reach this day and this moment, it has taken each of you at least three years and perhaps considerably more of law school studies to enable you to obtain your law degree today. You will have no more lectures and exams to endure.

And the faculty will no longer have you to endure. You will presumably begin to use your legal training in a variety of ways. Someone private practice, summon the public sector, summon business or a non legal pursues, but your thought processes, the way you approach and analyze problems is now forever changed. You've learned to break down complex issues into their component parts, and to look at them with some detachment and objectivity. You've learned how and where to try to find some answers. These are not insignificant achievements.

Now, it's a special day for me as well. This law school, as you know, was founded 103 years ago, in 1896, 24 years before women had the right to vote. Founded by two determined women, Ellen Spencer Mussey and Emma Gillett. Its first students first read, we're women. Since its beginning, the Washington College of Law has valued the role that women as well as men play as lawyers in our society. It has provided strong clinical programs to give students hands-on experience, helping those who needed to address legal issues. With its location in our nation's capital, it has provided special opportunities for students to work part-time to serve in public interest law programs to study international law, human rights and other specialties. From a beginning class of six women and an annual tuition of $40 to a class of 220 women and 167 men and an annual tuition of approximately $23,000, this law school has had a long and remarkable history. I'm truly delighted and honored to join you graduates in receiving a degree today from Washington College of Law. Thank you very much indeed.

Recently, my nine-year-old granddaughter visited me. We had a few days of sightseeing and grandmother-granddaughter bonding, a sort of cross-generational Emma family version of Thelma and Louise. And she is often on my mind. At one point during the visit, my granddaughter came to me disappointed about having to perform some task or other. "It was pointless," she said. Well, she didn't actually say pointless, pointless in the vocabulary of a young child is replaced by two words, but why, her meaning was clear nonetheless. Her second objection was that it was no fun. Pointless and no fun. One of my friends quipped, "If those were legitimate objections, we wouldn't have anyone practicing law." Well, look, comments seem funny at the time. But in retrospect, it's disconcerting. Is that what the practice of law has become? Pointless and no fun? It seems that in the eyes of many lawyers, it has. What is it you graduates are getting into, do you think? More than half of all practicing lawyers report dissatisfaction with the profession. According to one lawyer, the economic pressures of the legal marketplace have escalated workdays to a point where the practice of law is like drinking water from a fire hose. In this climate, attending to any professional obligations beyond the billable hours seems impossible.

Nor is dissatisfaction limited to those within the legal community in society at large, that is, among those few people in Washington, DC that we call non-lawyers. Lawyers are compared frequently and unfavorably with skunks, snakes, and sharks. You Americans remember the trust that our society once placed in its lawyers. It hardly seems possible that Alexis de Tocqueville, were he to come to America today, would still conclude that lawyers are our nation's natural aristocracy.

Partially responsible for this decline crisis back is a decline in professionalism. Dean Roscoe Pound once said that our profession is a group pursuing a learned art as a common calling in the spirit of public service, "no less a public service, because it may incidentally be a means of livelihood." And while my granddaughter undoubtedly is a far more interesting subject, what I really will talk about today for a very few minutes, is the obligations of professionalism, obligations in dealings with other lawyers, obligations toward legal institutions, and obligations to the public, whose interest lawyers must serve.

Personal relationships lie at the heart of the work that lawyers do. Even in the face of best technological advancements of the information age, the human dimension remains constant, and professional obligations will endure. It has been said that a nation and its laws are the expression of the highest ideals of its people. Unfortunately, the conduct of some of our nation's lawyers has sometimes been an expression of the lowest. Clients increasingly view lawyers as mere vendors of services, and law firms perceive themselves as businesses in a competitive marketplace. As the number of lawyers in this country approaches 1 million, the legal profession has narrowed its focus to the bottom line, to winning cases at all costs, to making large amounts of money. Almost every complaint about the decline of ethics and stability sounds the dirge of the profession. Turning into a trade, practice at the turn of the century, we are told, promises to be nasty, brutish, and for some, short. Now what are we going to do about it? What are you going to do about it? More stability and greater professionalism can only enhance the pleasure that lawyers find in practice, increase the effectiveness of our system of justice, and improve the public's perception of lawyers.

We've lost sight of a fundamental attribute of our profession, one that Shakespeare

who's so popular these days, described in The Taming of the Shrew. "Adversaries in law," he wrote, "strive mightily, but eat and drink as friends." In contemporary practice, sometimes we speak of our dealings with other lawyers as war, and too often lawyers act accordingly. The bench and the bar has begun to address the issue of professionalism in lawyer-lawyer relations. Codes of ethics in professional conduct are good starting points, and they are no doubt necessary, but they focus on what a lawyer should not do, rather than teaching lawyers what they affirmatively ought to do. But in the end, it is by deed, rather than decree, that attorneys teach each other that it is possible to disagree without being disagreeable. The first place where young lawyers can learn to disagree agreeably is right here in law school. Although there may be no remedy for the competitive nature of the law school, schools can do something about how that experience shapes the young lawyer's approach to practice. Good professors may employ the Socratic method, but not in the interests of disparaging students. Rather, they engage the students in dialogue, which although sometimes painful, helps students explore the law and develop critical thinking

skills.

Outside of class, students can learn collegiality

from an atmosphere in which each person

is treated with respect and understanding. Judges, too, play a crucial role in setting and enforcing high professional standards. They are role models for members of the legal profession, like that or not. Now, you may have noticed that I have not yet met head on my granddaughter's central question.

But why

there is a common frustration in the legal community, that all our long hours and our hard work are not producing anything socially worthwhile, in my view, both the special privileges

incident to membership and our profession. And the advantage those privileges give us in the necessary tasks about earning a living our means to a goal that transcends the accumulation of wealth. That goal is public service. It is this aspect of professionalism, service to the public, that I want to touch upon last.

Lawyers and judges have in our possession, the keys, the keys to justice under rule of law, the keys that can open the courtroom door. Those keys are not held

for the lawyer's own private purposes. They're held in trust for

everyone who would seek justice,

reaching for blacks and whites alike. We can be proud of the strides the legal community has made toward fulfilling that trust. The bar has never before been involved in greater amounts and more diverse types of pro bono service. Never before have law schools contributed so much by providing opportunities for their students to represent and advise

those who, but for those students, would have no access to legal advice or legal remedies. My law clerks tell me that those who participate in law school in these programs, remember those experiences long after they leave law school. That in practice,

later, they feel both an obligation and a desire to donate a portion of their time and their learning to public service. Yet despite progress and innovations of great and crime, need for legal services for the poor remains. In recent estimates, it suggests that as many as 85% of the legal needs of the poor, goes unmet.

There's evidence, very costly evidence, that a substantial number of citizens

believe that equality

is an unreliable slogan

, that justice is for just

us, the powerful, the educated, the privileged. A perception by too many that African-Americans and Hispanics are not accorded the same treatment in the judicial system, given other groups. If that perception is to be changed, and the factors that created it eliminated, the legal community must dedicate an even greater portion of its time and resources to public service. The ever-increasing pressure on the billable hour, combined with the tremendous emphasis on the bottom line, has made fulfilling the obligation to public service quite difficult. But public service marks the difference between a business and a profession. A business can focus only on progress. A profession cannot, it must focus first on the community it's supposed to serve.

And that community needs more legal help now than ever before. The notion that lawyers have a responsibility to their community, and that they're uniquely capable of making a contribution is nothing new. Lawyers were a critical group in the building of our own Constitution at the convention and 1787. Thirty-three of the 55 participants

were lawyers. When it proved necessary to drastically revise that document after the Civil War, once again lawyers were the dominant force. Thirteen of the 15 drafters of the 14th amendment were lawyers. It was lawyers who helped express our society's highest ideals in law

then. It is lawyers who must ensure that those ideals are realized and realizable now, not just for the well-to-do, but for the disenfranchised, and for the disadvantaged.

Now I wanted to finish

where I started, with my granddaughter, but she has yet to produce a great quote

about professionalism.

Give her time, she's still young. So I close instead with the words of John W. Davis. He was a former US Solicitor General, and an unsuccessful an unsuccessful candidate

for president.

But he spoke well. He reminded the legal community a bit sometimes humbled, but always professional role. This is what he said:

True, we build no bridges, we raise no towers, we construct no engines, we paint no pictures, there is little of all we do which the human eye can see. But we smooth out difficulties. We relieve stress. We correct mistakes. We take up other men and women's burdens, and by our efforts we make possible the peaceful life of men and women in a peaceful state.

At the Court on which I sit, we do not render advisory opinions, but I'm making an exception today and offering one specific piece of advice. As you enter the legal profession, I urge you to focus on the broader moral and ethical implications of your work as lawyers

.