David McKean

Of my colleagues and the director, tom putnam, I thank all of you for coming this evening. We count on your support and I encourage you to become a member of the library. Please visit our web site, jfklibrary. Org for more information. I would like to express particular thanks to the friends and institutions that make these forums possible. Bank of america, our lead sponsor of the kennedy library forum series, boston capital, the lowell institute and the boston foundation, along with our media sponsors, "the boston globe," wbur. We are honored to have with us tonight retired supreme court justices Sandra Day O'Connor and david souter. They are here to discuss their shared passion, the importance of civic education. Justice david souter recalls that when he was a boy, he learned the lessons of democracy and the functions of the three branches of government at new england town meetings. He's called those meetings the most radical exercise of american democracy that you can find. It didn't matter if someone or rich or poor, young or old, sensible or foolish, these meetings were governed by fundamental fairness. Today, when 2/3 of americans can't name the three branches of government, a rebirth of civic education is needed to assure, as justice souter has said, a nation of people who will stand up for individual rights against the popular will. Justice o'connor is even blunter. [laughter]. .

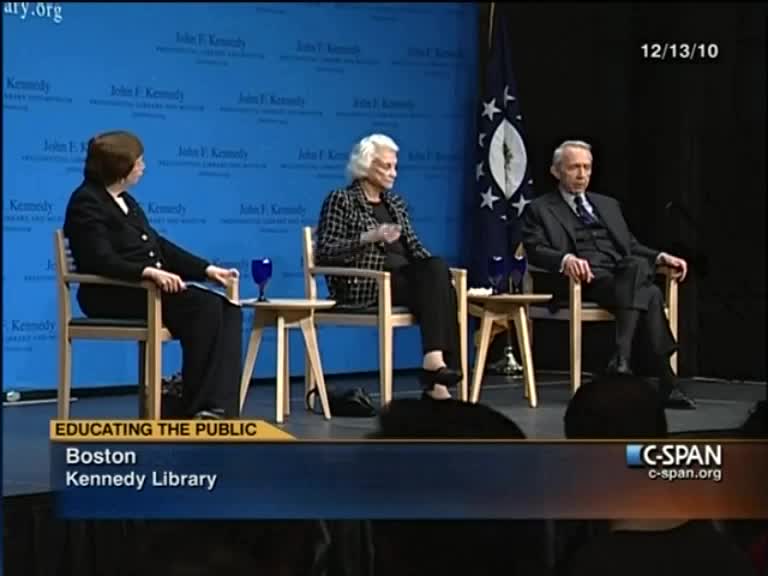

Justice o'connor retired from the court in 2005 and has been known to refer to herself as just as unemployed cowgirl. But as our moderator recently wrote in "the new york times," justice o'connor basically lives in airplanes traveling the country to support her causes. Let me read you one newspaper article that illustrates that commitment. In september, justice o'connor visited wrigley field in chicago to attend a cubs game wearing a royal blue cubs jacket, she delivered the game ball to the umpires on the field and then visited the broadcast booth. Where she delivered the following commentary, I never thought i'd see the day when we stopped teaching civics and government. It could be a little boring how they're teaching it but nonetheless it is an important function of the schools. . And then justice o'connor suddenly interrupted herself — ooh, big hit out there. You have to love a supreme court justice who jumps in to give the play-by-play at a cubs game. David souter was born in melrose, massachusetts and received his b. A. From harvard university and was a rhodes scholar in oxford before settling in new hampshire where he served as attorney general and on the state supreme court. He was nominated to the u. S. Supreme court in 1990 by president h. W. Bush — excuse me, george h. W. Bush. Our moderator also has written about justice souter. Just after he announced his retirement in 2009, she called him, quote, perfectly suited to his job. His polite, persistent questioning of lawyers who appear before the court display his preparation and mastery of the case at hand and the cases relevant to it. Far from being out of touch with the modern world, he is simply refused to surrender to it control over aspects of his own life that give him deep contentment, hiking, sailing, times with old friends, reading history. These days justice souter is doing some of the things he loves but he is also very occasionally speaking out about some important issues, at a commencement speech at harvard university this past may, justice souter spoke out about the different mode of constitutional interpretation. Ian deone said it was a philosophical shock that should be heard across the country. Our moderator, mrs. Greenhouse, is one of the foremost authorities on the supreme court, reporting on the court for "the new york times" from 1978-1998 she won the pulitzer prize in 1988 and now teaches at the law school. In a recent op-ed about the three former justices, john paul stevens, sand a a day o'connor and david souter she noted their shared capacity for blunt talk and of tonight's speakers she writes, free from the structures of incumbency and the need to garner votes, each is in a public position to help the public understand a bit more about how a supreme court justice thinks. As well as about the supreme court itself, its processes and its challenges. With that in mind, please join me in welcoming justice Sandra Day O'Connor, justice david souter and our moderator Linda Greenhouse. [applause]

Linda Greenhouse

Thank you. It's a personal thrill to be here, really, here in the kennedy library on the 50th anniversary of his election. I was a young teenager at that time and I have to say that he did inspire my own interest in public affairs and the public live life — public life of the country and I remember my friend and I in school hanging on every development of the 1960 campaign and the startup of the new administration and that's kind of a deliberate segue into our topic tonight which is the civics education deficit in the country's schools, you know, just kind of makes me wonder whether the same energy and enthusiasm with which I and my 12 and 13-year-old friends in 1960 approached what was going on in the country based on some knowledge of what we had been taught in public school, whether that still exists today. So I'll just start off by asking both of you, since you made this really a project of your — of this phase of your professional careers, what motivated you to choose this topic to really devote yourself to? we started public schools in this country in the early 1,800's on the basis

Sandra Day O'Connor

Of arguments, but we had an obligation to teach our young people how our government worked so they could be part of making it work in the future. That was the whole idea. That was the justification to getting public schools in this country. And I went to school — there weren't any out on the lazy b ranch so I was packed off to my grandmother in el paso, and went to school there and I had a lot of civics but it was largely texas. I got so tired of steven f. Austin, I never wanted to hear another word about him. It was just endless.

Hearing about the alamo doesn't help much.

No, I wasn't? san antonio, we went el paso. So anyway, we had a lot of civics in my day, and I guess I just thought that was what schools were supposed to do. And I was stunned to learn that half the states no longer makes civics and government a retirement, no longer. And we had a lot of concern about what young people were learning and I can understand why some of it was getting boring. The leading text book for civics was 790 pages long. Now, I'm sorry, you can't give that to some young person and expect them to just read it and absorb it. It doesn't happen. So I felt we needed a little help. And that's how I got

David H. Souter

Involved.

And you recruited your colleague.

Well, yes. She got me into this. I mean really, she did. I didn't have any particular sense of what was going on in civics teaching in the united states. I remembered mine, but five to six years ago, justice o'connor and justice breyer convened a conference in washington to address the threats to judicial independence which seemed to be snowballing at the time. And the most significant thing and the most shocking thing I think that I learned the first day that we were there was the statistic that you've already heard this evening that depending on who does the measuring, only about 2/3 at best 60% of the people in the united states, can name three branches of government. They simply are unaware of a tripod type scheme of government and a separation of powers. The implication of that for judicial independence is that if one does not know about three branches of government, and the distinctive obligations of each branch, then talking about judicial independence makes absolutely no sense whatever. Independence why? independence from what? independence for what reason? you get absolutely nowhere because there is not a common basis in knowledge for discourse. And when I and others left that meeting, we realized that yeah, we had a lot to worry about on attacks on judicial independence, but we had a broader problem to worry about in the united states, and I have only become more convinced that it is a serious problem, not a kind of chicken little problem or a reflection of nose taling yeah of dinosaurs — nostalgia of dinosaurs the way government was taught when we were kids. But my awakeness started at that conference on judicial independence.

There's one other part of this story that I thought was disturbing, american high school students were tested along with 20 other nations a few years ago and they were — they came in near the bottom of the 20 nations in scores on math and science.

Sandra Day O'Connor

And it was so frightening that our then president and congress said we had to do something. That means money, federal money. So they put together federal money to give to schools based on good test scores in those schools for math and science and reading.

You're talking about no child left behind.

No child left behind. You've heard of that, and that was the program. And no doubt a good thing but the problem was that it turned out that because none of the federal money was given to teach civics or american history or government, the schools started dropping it and half the states today no longer make civics and government a requirement for high school. Only three states in the united states require it for middle school. I mean, we're in bad shape and we need to do something.

You are doing something.

We

David H. Souter

Are.

The relevance of no child left behind today I think is indicated by what justice o'connor said, we've got a kind of testing culture in america's schools which is all the good on subjects of science, reading and math which are being tested, the effectiveness I don't know, but the objective is obviously ok. The trouble is that as everybody says, schools have a tendency to teach to the test. And if finances or educational ratings or other sort of measures of decency and excellence are going to be tied to the tests on these three subjects, the natural human tendency is everything else will be short shrift. We have to be careful not to suggest that no child left behind is the source of the problem because american schools started dropping the teaching of civics as we remember it back around 1970. There was a series of conclusions drawn by educators to the effect that teaching civics really had no affect, in fact, on what people — what young adult people ended up knowing about their government. This seems counterintuitive, but that was the theory and that's why civics started getting dropped. The problem with no child left behind for those who want to revitalize civics education, you've got too find room in the school day to fit it in and your competitor is in effect no child left behind in the subjects which are getting tested. That suggests an ultimately pragmatic solution and that is you've got to start testing on civics.

Right.

And the only good news, I guess, in this particular tension, is that there is an absolute tension in fulfilling no child left behind and finding time for civics. The fact is, a lot, for example, of the material take can be used to the civic segment of no child left behind can be civics reading, not 700 pages at a time but there's a way to infiltrate no child left behind with some civics. The problem has to be faced on how you provide an incentive to the school administration and the school districts to work this in. And I use the reference to administration advisedly because one thing i've learned just from being on a group in new hampshire that is trying to beef things up up there is that the civics teachers are out there and they're dying to teach, and I happen to have met some, both on the grade school level and high school level. And you know, they're raring to go. We do not have a problem of conversion among teachers. And what we've got to do is find a way to find room in a finite school day to get this done. And as I said, at the end of the line, we've got to have — people don't like to use the word "testing" anymore. They like to talk about accountability. And — but we've got to get a civics test squeezed back in.

You're directly involved in a curriculum reform effort in new hampshire.

Yeah.

Tell us a bit about that.

Well, I'm a johnny-come-lately to it in a way because it was a group formed by an organization called new hampshire supreme court society, which is what of a historical society but of the new hampshire supreme court but a society that wants to have some public relevance beyond even the teaching of history. And it took up as a project actually before I had retired, a review of new hampshire curricula practice and the question, is there something useful we can do? and that process of examination, as I said, I joined up when I left washington. And I have at this point a fairly good sense of what is going on in new hampshire schools. I've met some teachers and actually met a bunch of kids, some classes i've gone to. And I think, by the way, to just not leave the subject hanging, what a group like mine can do and what I suspect a group like mine can do probably in most states is not convince teachers that they ought to teach civics, that's there, at least in new hampshire experience, we don't have to sell them on that. What we have to do is provide in effect the whole teaching apparatus, an incentive to make room for this. And the second thing we've got to do is provide them with some materials to teach from. There simply is not readily available standardized universally accepted text books of the sort, I think I remember, of course there is no testing. New hampshire, like most states dropped testing from civics. And we've also got to provide, if we can do it and raise some money to do it, a kind of continuing education scheme for the teachers of civics to get them together, very much like the supreme court of the united states is historical society does for teachers of constitutional history. And give them some beefed up education of their own which they are dying to have. So that's where I think we can do something useful. And my guess is that what is missing in new hampshire and what would be accepted by the educational systems in new hampshire is probably going to be true in most states.

So the effort would be to kind of model some best practices that could be exported?

I've got another idea.

I'm sure you do. [laughter]

You wonder why we write concurring opinions

Sandra Day O'Connor

Now.

I think young people today like to spend time in front of computer screens and videos. And in fact, they spend on the average 40 hours a week doing that, if you can believe it. That's more time than they spend with parents or in school. And so I think we have to capture some of that. And i've been — have organized a program to do that and to put the material for civics education in a series of games that kids can play on computers. And believe me, they love it. And if you want to look at it and if any teacher wants to look at it, it's www. Icivics. Org. And it is, if I have to say so, fabulous. It really is.

Actually in preparing for this —

I have heard other people say that, too.

Justice souter doesn't actually have a computer, so this is all by mouth.

That's why I said other people.

But I did go on the website and it's very engaging and comes with curricular guides so teachers can use it as real material. I went on to one about the judicial system and it's a series of actual supreme court cases where there's ways that you click on the various arguments and the students are asked to pick the best argument to such such and such a proposition. And it's really — I found myself really getting into it.

It's really a success, I think, and can be except, do you know what the worst bureaucracy in our country is today? it's the schools.

Linda Greenhouse

Sandra Day O'Connor

They're in 50 states there is not one state where there is one person in that state who can tell the schools what to do and they have to do it. Not one. We are organized with separate individual school districts. We have close to, you know — many hundreds in my little state of arizona. And so to get something like this conveyed to all the schools means you have to contact each one, and it's kind of a nightmare. That's what we're running into with my program, how do you get everybody acquainted? so I have chair people now in 49 of the 50 states. Now, whether they'll succeed in contacting all of the schools remains to be seen. Maybe you can volunteer. Let me hear from you.

How closely have you been involved in actually doing the gaming and deciding what needs to be —

I actually sat with some and previewed some and made suggestions on some. I mean, i've not — we have experts like mcarthur genius award-winners who are better at doing this, but I have participated in some to figure out what we have got to do or not do.

Justice souter talks about the impact of the deficit and knowledge about the courts, and obviously that's one thing.

Linda Greenhouse

Are there other particular deficits that you've noticed as you've talked to people or followed this issue?

No knowledge.

Yeah.

It's total. To start with, they don't know their three branches of government. We've already covered that. And even if they

Sandra Day O'Connor

Do, how to course work, what do they do, who is in charge, how do they approach cases. In the case of congress, they don't know how things happen.

I don't either.

Well, not much does, I guess. Now and then there's a little trickle down somewhere. Anyway, we know what's supposed to happen. And so there's a lot to teach, a lot to learn.

And things really have changed, again, from the time when we were kids. When I say things have changed, not merely the dropping of teaching but the resulting deficit. One of the difficulties in — at least that i've found in trying to put all of this in perspective is that we have much better studies about what's going on today than we had about what was going on 50 years ago. People weren't making the same kind of surveys, at least I haven't run into them, but I have been impressed

David H. Souter

With one summary which went through a series of rather detailed survey findings in the mid 1990's. And the conclusions to be drawn from it were summarized by one of the educators in the field named william gallton he — william galston, he said the numbers seemed to show that the degree of civic and broader political knowledge on behalf of a high school graduate in the mid 1990's was equivalent to that of a high school dropout in the 1940's.

Wow.

And the degree, again, of com probable knowledge of a college graduate in the mid 1990'ses — 190's, was about that of a high school graduate in the 1940's. And if anything needs — can further be said to underline what is shocking and disparitying to that is during the same period of time, the growth in the availability of higher education was explosive. And yet in effect what we said is the level of collegiate knowledge dropped to high school and high school dropped to dropout. Something really bad has happened.

In preparing for this, I kind of cast a wide net and tried to find some other resources that are out there just to get a sense of how broadly this problem is being recognized and actually there's a lot going on.

Oh, yeah.

I noticed richard dreyfus, the actor, has weighed in on this. He set something up called the dreyfus initiative which is the curricular development program. I looked at that website.

Linda Greenhouse

And then on the judicial system in maine, a coalition of the federal and state judges organizes the maine federal state judicial council has started a program of video interviews of judges talking about their life and work. And it's really engaging. They had one judge, a state judge, I can't think of his name, who talked about being a troublemaker in high school and dropping out of college and taking a long time to get his act together and eventually obviously becoming a judge. But the point was to make the judiciary not seem something remote, people are born with their ropes on or something.

Right.

But to give citizens the sense that these are real people doing a job for the public who are, you know, more or less approachable and can be sort of understood on a human level. And I wonder just looking at the supreme court, for instance, we seem to be in an era where a number of justices are — current as well as retired, are out and about and making the court a little more accessible. And you both have been around long enough to see that as a trend, this wasn't something that was so true when both of you became judges, and i'd just be interested in your reflection whether there's anything the supreme court itself either institutionally or individual justices can do to address this.

It was interesting because I'm not in washington, d. C.

Sandra Day O'Connor

All the time anymore, just now and then. And I respectly was there and I sat in the courtroom to watch an oral argument and sat there and looked up at the bench, nine positions. And it was absolutely incredible. On the far right was a woman, boom, boom, boom, near the middle there was a woman. On the far left was a woman. Three of them. Now, think of it it. It was incredible. And it took 191 years to get the first. And we're building a little more rapidly now. I'm pretty impressed.

Heck, look at this group here. I'm the diversity. [laughter] [applause]

So things are happening.

Extrapolate from what you said, the court being able to sort of model.

I just think that the image that americans overall have of the court have to change a little bit when they look up there and see what I saw. I thought that was a pretty big change.

Not many people get a chance to actually —

You know, everybody takes pictures of the court.

Here we are on c-span and c-span has kind of a dog in that fight. Of why don't you bring the court in the living room for the america.

A fight which I hope c-span loses.

Well, we won't go off on

Linda Greenhouse

That. But looking at the election this fall on some of the judicial issues. For instance, what happened in iowa where sitting judges were thrown out in their retention elections.

Now that is another subject on which i've been trying to be helpful.

Sandra Day O'Connor

How we select state court judges. Now, this is a really important topic. And it seems to me that many of the states need to consider some changes. When we started out, the framers of the constitution got busy and designed the federal system. And when they came to the judicial branch, they provided the judges would be appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the senate, no election of the judges, right? no election. And the original 13 states all had similar systems. I mean, closely related to that. Now, a few years went by and all of a sudden we had andrew jackson and he stated this down in new orleans. That was good. But you know what he did, he didn't say we should elect our state judges and he was the one who went through and said you have to change and elect your judges. The first state to do that was georgia. A bunch of others followed suit and now what do we have? we have this hodgepodge and many states, I think about 20, still have popular election of the state court judges and that means campaign contributions, they run for office, who gives them money? the lawyers who appear before them, some of the clients that appear before them. There was that case the supreme court had from west virginia, big judge hunt against the massey coal company, $50 million or something of the sort. And the chairman of massey coals wanted that — that judgment was in a trial court in west virginia. And in west virginia, they just have two levels of court, the trial court and supreme court. And massey wanted to appeal to the supreme court. That's fine. It's a five-member court and there was going to be an election the next general election and one member of the court had to run for office, his time was up. Well, massey, co-chairman, gave the man about $3 million to help with his election campaign in the state of west virginia. And guess what? he won. Big surprise. Then the case was heard and somebody on the other side said to the re-elected justice. Maybe you should recuse yourself because of these — oh, no, I can be fair. So I heard the case and in a 3-2 decision did not — he voted to overturn the judgment against pasi with the participation, a 3-2 decision of this newly elected judge and the other side signed a petition to the u. S. Supreme court saying we were denied due process here. That's a hard claim to make. I'm glad I wasn't sitting on the court for that case. That's tough. But the court ultimately decided that was correct. There was a due process denial and that means states are going to have to be a little more careful with how — about how they organize their courts and that was the right signal to send but many states still have their election of judges and that's not a good idea. I would like to see more states select a merit selection system where there is a bipartisan citizens commission formed that will receive applications from people who want to be a judge, review them, interview the people, make recommendations to the governor who can appoint from the list of recommended people and then tip lick in those so systems they will serve for something like 16 years and then stand for retention election. That's what happened in iowa. Their supreme court is a merit selection system court and three of the justices were up for resense elections. The court had unanimously decided a case involving a gay marriage law which irritated some voters in that state and they campaigned against these judges with the retention and a majority of the voters voted them out and said no, we don't want to keep them.

Linda Greenhouse

That was a big signal.

I wanted to ask you about that because the so-called missouri plan, the merit election and retention has been held up for years by you and others as the preferable way to go. And what happened in iowa, yes, some voters didn't like the outcome of the same-sex marriage case but I think kind of more to the point, outside groups came in to use the election to teach a lesson.

Correct.

Spent a lot of money, the judges running for retention have never pondered anything like that.

And they didn't do much in response.

When was part of the problem. It hazes the question of these days, very aggressive, money-laden campaigns, whether the missouri plan still holds up as a civic improvement?

It does. It does. And arizona has it, and I watched the process there. It doesn't mean you can't have a problem, you can. It is so much better than the alternative, you can't imagine. But it tells me you have to be aware and if there's something that happened in iowa, those hoping to be retained better be asking and do something in response.

So they need campaign committees and contributions.

If there's going to be a major effort, yes.

So you're kind of back in the soup.

Well, not as bad because you get over the hump and then go back to where it was. It's not going to happen every time.

To draw a leaf between that and the problem, do you think if the public has a better understanding of the judiciary through some sort of education this sort of thing could be mitigated in some way or it's an issue, had enough, does it just kind of overwhelm?

Well, occasionally there will be a hot issue and in our country it tends to turn on abortion or gay marriage or something like that and voters can get pretty excited about some of those issues.

Justice souter, you were a state judge for years in your career. Now, you were appointed.

I was appointed, yeah.

David H. Souter

And without a retention election.

That's right.

New hampshire is plain old —

The federal system except there's a mandatory retirement in new hampshire. So I didn't have to face that. But I agree with justice o'connor, if you're going to have an elective system, try to have the missouri plan. That's the best way. You still can't make a silk purse out of a sow's ear but you're along the way a bit. The missouri plan and in any system, even with retention elections is intentioned with the fundamental understanding that animates an appointed system with life or long-term appointment and that is the understanding that when the heat is on we tend to do the wrong thing. We get excited, our judgment evaporates, and that is where why — and that is why you want a branch of government which has reference to principles that are going to endure beyond the heat of the moment to say wait a minute, you just violated your own rules. And if you cannot have a branch of government with the power to do that and with the incentive to do it, nothing that those who make the declaration will not be thrown out on the street the next morning, you in fact are compromising the very concept behind the rule of law and the rule of enduring law. So that's the fundamental problem even under a missouri plan. The development that exacerbated that problem is the development of money in judicial elections which has in its turn been exacerbated by the recent development in the law which took place after both justice o'connor's and my departure but on which we expressed opinions earlier, to the effect that corporations cannot be limited in the kind of expenditures that they make for political purposes. And if that were not sufficient exacerbation, that combined with the legal avenues now for disguising the sources of political contributions makes for a, a very general threat to political integrity and a particular one to the judiciary. How does the judiciary respond? the judiciary is political and can't do anything about it, but there is one authority that the judiciary has got to start thinking of using because I assume the occasion is going to arise. Think back for a second to justice o'connor's reference to the west virginia election case. The reason that case in one way was easy to focus, the reason the issue could easily be focused was that it was a matter of public record where the $3 million came from. It came from, I forget the president or the chairman, I think you said, of the company which was appealing the very large verdict against him. What does the litigant do now in a state of elected judges when in effect as a matter of federal law the limits are off on what corporations can do and in fact are avenues of contribution which do not disclose the ultimate source of the money. It seems to me I know what I would do if I were a litigant in that kind of situation, I would require a — I would demand in the name of due process a disclosure of all contributions on that court of which I was going to appear and an analysis of the sources if in fact the named source was or might be opaque. And I think it's inevitable this is going to come. And I don't know really of anything that litigants can do in the name of due process short of this. Unless they are willing to take the chance of just being a fish shot at in a barrel and they don't know who's firing. I think this has got to come.

I do, too.

Where this is leading, I think, given the current supreme court majority's view of the first amendment is the clash between the first amendment and due process.

Which, you're right. But, you know, this oversimplifies a little bit but not by an awful lot most of the constitutional issues that come before the supreme court of the united states are not questions of should we apply this principle as it logically ought to be applied, but rather questions of should we apply this principle that might apply, or that plinnle — principle that might apply? the essence of principled decisionmaking by a court like the supreme court of the united states i