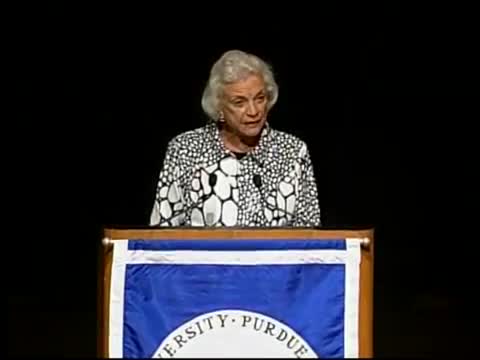

Sandra Day O'Connor

Thank you, thank you. You have to sit down because this is long. You're gonna need your rest, I think. I thought this was supposed to be a very serious event. So no Comedy Central tonight, you're gonna have to concentrate. But we'll have a question and answer time at the end, and maybe that'll be a little lively. My topic is advancing the rights of humanity. And it is a privilege to take part in this Omnibus lecture series. It's a wonderful program that's gone on for more than a decade, and it has cultivated the exploration of a good many issues and a great many ideas.

You've attracted an impressive list of speakers over the years, and you've gained the participation of not only the academic community but the larger community in which you make your homes. And these are good achievements, and I'm very pleased to be part of it. This year is particularly special. In conjunction with this lecture series, you're hosting a collection of documents on loan from the Remnant Trust, as you've heard, and that includes original and first edition works dealing with the topics of liberty and dignity. Some of the items in the collection date as early as 1250 AD, and it does include some of the most celebrated works on these themes by many distinguished thinkers in the past. It includes a copy of the Magna Carta, Cato's letters, a copy of the Declaration of Independence, Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Women, a copy of the Gettysburg Address, and many more. So it's a challenge to present a lecture in the shadow of these works. I'll try. And my topic is advancing the rights of humanity. I'm going to focus on some written works published more recently than those on loan from the remnant trust.

I'm going to focus on some opinions of the United States Supreme Court in the last 60 years or so. Not all of them, don't worry, not that many.

But these opinions nicely tell the story of our country's commitment to civil rights. It's a commitment that's relatively recent, but I think it's growing stronger. I think the Supreme Court had a lot to do with this progress. And that's the main point I want to make tonight. America's worst year We're clearly those of the Civil War. In the decades that follow the Civil War, American society was deeply and officially segregated by race. Blacks could not sit with whites in restaurants or on buses. They could not buy homes next or whites. They could not even attend public schools with white children. Women have not attained the right to vote. The courts have not recognized this intrinsic importance of freedom of speech and expression, or of a free press or religious freedom.

The Bill of Rights, which was approved in 1791 was considered applicable only to the federal government and not to the state and local governments. were mostly most of the treatment of criminal suspects and defendants took place. And today all of that is changed largely because of cases and decisions on individual constitutional rights handed down by the Supreme Court of the United States in the last half of the 20th century. And those rulings and the nation's response to them are the defining moments of the legal system, in this century just ended the 20th century. Some people if they think of the Supreme Court at all, and most don't think of it in its late 20th century role as the defender and sometimes creative, of individual rights. For much of its history, though, the Supreme Court had little to say about the Constitution guarantees and the individual freedoms. At the turn of the 19th century, the docket of the Supreme Court was dominated by private issues, that constitutional questions the court did decide, concern the division of authority between the states and the federal government and the allocation of power among the branches of the federal government. But as the 20th century progressed, evolving notions of individual liberty, and efforts to balance that Liberty with governmental power and the commands of citizenship became the very heart of judicial decision making at the Supreme Court. Now, why did the Supreme Court assume that on a custom role, and how we're this nation's historical promises of equality suddenly brought to fruition?

In the early 1900s, wounds from the Civil War were still here, while waves of immigration rapidly expanded both the size and the diversity of our country's population. By the middle of the 20th century, when individual liberties came to the forefront of our national consciousness, our country had also endured two world wars. Service in the military managed to merge different ethnic and racial groups and prompted them to imagine the ways in which maybe they could live and work together in peacetime as well as in more. And women who did not even gain the right to vote in the United States until the 19th. amendment in 1920. Women also had been integrated into the workplace during the wars because the men went off to fight and the women took the jobs and the changing face of the population. The forever altered role of women and the hopes and expectations of a new generation of racial and ethnic minorities prompted the civil rights movement in mid century. Now much of that movement centered on litigation at the United States Supreme Court, and the range of rulings that emerged had a profound impact on our country.

In the past 50 years, the Supreme Court's decisions on individual rights have recognized for the first time many of the freedoms that Americans today just assume our birthright, among them are the right to speak freely and advocate for change the right to worship as we please. the privilege of political participation. For example, not until the 1960s did the did the court acknowledge the constitutional right of the media media to criticize public officials. And it was in that era that the court first guaranteed all indigent criminal defendants the assistance of a lawyer at public expense if they couldn't afford it, and the court applied the protection against self incriminating to defendants in state courts, as well as federal courts. The court recognize the right to confront and cross-examined witnesses in state trials as well as federal and obliged the states to give a speedy trial to criminal defendants and our jury trial to those accused of serious crimes. And the court extended the ban on double jeopardy to state criminal proceedings in the 1960s and 70s.

The court also struggled with issues of personal privacy and procreative freedom, addressing in Roe versus Wade a question that has deeply divided and still divides the American public: whether and to what extent the Constitution protects a woman's choice to have an abortion. And under the equal protection clause, the court began to strike down laws and regulations that discriminated on the basis of gender, as well as interpreting federal statutes to prohibit employment discrimination against women and to provide protection from sexual harassment in the workplace.

Now the centerpiece of this Supreme Court's decisions on individual rights, the centerpiece is Brown versus Board of Education, which mandated the desegregation of public schools just over a half a century before that case. Plessey v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court had held that Louisiana's requirement of separate but equal accommodations for black and white passengers on railroad trains was consistent with the Constitution. But in 1944, the court announced that it would give closer scrutiny to laws that treated one race differently from another. Shortly after that, the Court declared unconstitutional the exclusion of blacks from state primary elections and prohibited job discrimination against black railroad workers. And the court struck down a restrictive covenant that prevented black citizens from choosing certain neighborhoods in which to live. It was those decisions that led up to the unanimous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. By that ruling, the court once and for all abandoned the idea that separate public accommodations could be equal once. Brown became the basis for subsequent decisions striking down different forms of segregation through the south, in parks, beaches, traffic courts, theaters, railroad cars, bus terminals. And with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prompted in large part by the real social upheaval that followed that brown decision, the Supreme Court and Congress finally acknowledged the need to give meaning to their promise by our framers of the Constitution, the promise of equality, although by then in a richly diverse nation that the authors of the Bill of Rights could never have envisioned.

Now, once judicial review became the tool for implementing reform and change, the courts acknowledgement of a particular legal right often would lead other litigants to put forward their claims to new and different rights. The imperative to accord equal treatment without regard to race or gender has led to second generation problems in defining the proper remedies for previous discrimination. Recently, there have been challenges to affirmative action to correct prior discrimination in the workplace and in the schools. Housing demographics have led to partial de facto re segregation of some schools and some plaintiffs at the condom have started to challenge the appropriateness of legislative and court ordered remedies that favor minorities, and best depart from the colorblind aspirations for our society that were first expressed in the brown decision. will certainly there is still much work left to be done in the United States to erase the damage of distress caused by previous racial discrimination. And many questions remain unanswered about the ultimate sweep of the courts and individual rights decisions. But I do believe that the hallmark of social change in the last century was the Supreme Court's increasing protection of the individual and its efforts to extend the benefits of American citizenship to every segment of our society.

Now, I want to turn to the new 21st century and turn from the rights of our citizens to a few of the rights of our enemies of all things. One important aspect of the Supreme Court's role in developing and guarding civil rights is that it is most often carried out through decisions that hold unconstitutional the actions of other governmental entities. civil liberties are born, as the court rejects laws enacted by state and federal legislators. And when the court limits the authority of state and federal executives, for example, Brown was a decision that struck down eight Kansas law and similar laws, other states and the Fourth Amendment protections we're doing develop through a series of decisions, invalidating the actions of state and federal law enforcement officials. And this dynamic is central to the design of our three part federal system of government, the design of our frames, principles of federalism,

separate power between state governments and our federal government. But the Constitution, of course, is a paramount limitation on all government authority. And the Supreme Court bears the ultimate responsibility of enforcing that constitutional guarantees. And within the federal system, power is carefully balanced between the Congress, the President, and the judicial branch. But it is again the Supreme Court that has ultra responsibility in ruling on the constitutionality of many federal actions. Now, this often puts the Supreme Court in a delicate position. It's the Constitution itself, that spells out the sphere of power of each of our three branches of government. And as the court defense civil rights against the actions of other branches of government, the court has to remain mindful of its role in our overarching system of government. For example, the Constitution is very clear that the President of the United States has great authority and much autonomy in fighting wars. We've been watching that recently. Evidently.

The court has to respect that authority when it passes judgment on the President's sections in this capacity. The Constitution similarly gives Congress important authority to check presidential war making power. When Congress endorses the actions of the President, the Supreme Court has even greater reason to defer judgments that underlie those actions and defer to those judgments. Put another way that court has to tread most carefully, when it finds itself out voted to the one when the President and the Congress are united, and of course of action that the court might find unconstitutional. And this is especially so when the action at issue like conducting wars is uniquely within the province of the other branches. This doesn't happen too often. But it tends to happen when core civil rights are threatened. This makes good sense. The court can be most confident of the necessity of its intervention. When the rights of issue or most fundamental, now are generally, the best strategy for the Supreme Court, when it's placed in this bench is to act carefully and incrementally. It should give ample opportunity to the other branches to make their own corrections to decide how best to respond to the constitutional roadblock.

The Supreme Court's recent efforts to recognize and defend the civil rights of those persons designated as enemy combatants by the president is a good example of this strategy at work. The Court fulfilled its obligation to enforce strictures of the Constitution through incremental yet deliberate decisions. And these decisions left room for the other branches to respond to control the means by which to align our conduct of war within the Constitution's guaranteed guarantees. Ultimately, I think this approach bore fruit. But that's the story I want to sketch for you. And I'm going to start by describing a conflict between the executive and judicial branches of the US government.

Not long after the outbreak of war, the President of the United States altered the traditional understanding of civil liberties by finding that standard jury trials could not meet the necessities of wartime. In an effort to remedy the situation, the chief executive determined that some defendants should be tried by special military courts rather than traditional juries. The United States Supreme Court rejected that idea, however, finding that the military courts lacked jurisdiction over the defendants who were US citizens.

Now, this conflict sounds as though it comes directly from recent pages of the New York Times. But the events I just described predate the birth of that newspaper. Instead of describing President George Bush and the War on Terror, I just described President Abraham Lincoln and our Civil War of the 1860s. President Lincoln decided that wartime needs required him to suspend the constitutional right to a writ of habeas corpus. In Ex parte Milligan, our Supreme Court held that military tribunals did not have jurisdiction of civilians who were suspected of aiding the Confederacy so long as the traditional civilian courts remained open and functioning. Justice David Davis's opinion for the Supreme Court noted, in language that has taken on new resonance today, that "the Constitution provides law for rulers and people equally in times of war and peace."

Now, I started on this historical note, because it is important to remember that this is not the first age or time in which governments have considered how best to strike that delicate balance between protecting civil liberties on one man and protecting national security on the other. There are distinctly novel aspects to our modern struggle against terrorism. But there's continuity, in addition to change. History doesn't give us all the legal answers, but it often helps us at least and asking the right legal questions. We have to be skeptical of arguments that trying to minimize the very real dangers of the present conflict we face, called quite some time has passed since a terrorist attack occurred within the United States. The absence of an attack does not mean the enemy has been vanquished.

About two years ago, several deadly car bombs were discovered in densely populated areas of London. Attacks against airports and the UK and in Germany were narrowly averted. Suicide bombings have been have become so commonplace in parts of the world that they don't even make the nightly news. And those who would make no restrictions on personal liberties, might do well to remember the thoughts that US Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson expressed in a dissenting opinion in a case involving the freedom of speech. "The choice is not between order and liberty," Justice Jackson wrote, "it is between liberty with order and anarchy without either." Justice Jackson famously warned that unqualified demands for liberty threatened to convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.

Well, looking at the past reveals that the United States has not always struck the right balance between national security and civil liberties. Maybe the most disturbing example of a failure to safeguard civil liberties was illustrated in that case called Korematsu v. United States. In that case from World War Two, our Supreme Court considered whether American-born citizens of Japanese descent could be put into internment camps because of their ancestral background. Although Justice Hugo Black's opinion for the Supreme Court conceded that all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single group are immediately suspect, he nonetheless found that national security demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the west coast. Now Justice Jackson again in dissent, contended that placement of the Court's imprimatur on the internment camps struck a deep blow against liberty. "Once judicial opinion rationalizes such an order to show that it conforms to the Constitution, the Court for all the time has validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure and of transplanting American citizens." The Korematsu opinion, Justice Jackson feared, "lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim to an urgent need."

Well, since World War Two, thankfully,

no official of our government has reached for that loaded weapon. Even in our current time of anxiety, it has not been proposed that we remove the liberty of an entire group of our citizens solely because of their race, religion, ancestry or something combination of it. Korematsu appears, maybe, to be dead letter law. That the September 11 attacks, produced fear and terror is well known. But those attacks also produced legislation, both in the United States and abroad. Legislation designed to combat terrorism. That legislation is working its way through legal systems around the world, our own and that of other countries. In the wake of September 11, the legislative and executive branches of the United States took a number of steps to act against terrorism. Congress adopted the Authorized Use of Military Force (AUMF is the acronym), which gave the president authority to US military force against the entities responsible for the attacks. It also gave the president authority to prevent future terrorist attacks.

Using this law, the president sent us troops to Afghanistan to wage war against al Qaeda and the Taliban. The President also set up a detention center at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, and established protocols to deal with the detainees there. And these actions have prompted four major Supreme Court decisions concerning our war on terror. They are type: entry-hyperlink id: hamdi-v-rumsfeld-2003, Rasul v. Bush, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, and the latest, Boumediene v. Bush. In the first of these cases, I'm DR. Supreme Court considered the case Yasir Hamdi, an American-born citizen who was captured on a battlefield in Afghanistan. He was brought back to the US and designated an enemy combatant. Hamdi's father filed a lawsuit contending that his son should be permitted to challenge that designation. The court, in an opinion which I authored, that was before I retired, held that a citizen detainee seeking to challenge his classification as an enemy combatant must receive notice of the factual basis for his classification and a fair opportunity to rebut the government's factual assertions before a neutral decision-maker. The Court also expressed skepticism regarding the government's contention that principles of separation of powers necessarily limits the judiciary's role. During the war on terror, we noted that "a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to rights of the nation's citizens."

Now, the second of the cases, Rasul v. Bush involved people who are not citizens of the United States. Rasul was a habeas corpus application brought on behalf of several Guantanamo Bay detainees, including citizens of some member states of the European Union, who are captured on a battlefield in Afghanistan. The executive branch of our government said these people had no right to challenge their detainment because they were non citizens caught on a foreign battlefield. And they were being held outside us borders, namely in Guantanamo Bay. The Supreme Court in that case held at federal courts do in fact cap jurisdiction to determine the legality of the executives potentially indefinite detention. The individuals who claim to be wholly innocent of wrongdoing it held at Guantanamo Bay is within the jurisdiction of us courts for this purpose.

The court considered this issue again in June 2006. In a case called Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. This time their president argued that an act of Congress that detainee Treatment Act strip the courts in this country have the authority to review habeas corpus challenges brought by detainees. The President also argued that the act granted the President the authority to establish military tribunals to try the detainees and to limit great The rights of detainees in those proceedings. The court read the detainee Treatment Act not to interfere with courts authority to hear challenges brought by detainees. The court determined that Congress had authorized the executive branch to try suspected terrorists in military tribunals only in exceptional circumstances. But the court set the standard procedural rules of courts martial as the baseline to be used in such trials, rather than the more limited rights that government had provided. And while the administration is permitted to change or adapt those rules, it has to demonstrate that using the standard courts martial rules would be impractical. Four members of the court in the Hamdan case also wrote they thought the proposed military tribunals violated article three of the Geneva Conventions, which requires that criminal sentences be issued by a regularly constituted court, affording the judicial guarantees recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

Now, after the Supreme Court decided hummed on, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act, which some argued repealed all jurisdiction of the federal courts over claims of those who were designated as enemy combatants. Prisoners in Guantanamo had filed habeas corpus petitions, questioning their detainment. And the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit said it lacked jurisdiction over those cases under the Military Commissions Act and dismissed them.

In June 2008, the Supreme Court addressed this issue in the case of Boumediene v. Bush. This time, the Court agreed that Congress had tried to strip courts of their authority to hear habeas corpus challenges brought by the detainees. But it also held that that action was unconstitutional. The court concluded that the United States exercise of authority over Guantanamo Bay gave the detainees the right to bring claims of habeas corpus in federal district courts. The Supreme Court also held that the procedures authorized under the Military Commission Act, which authorized tribunals to look into the detention of the detainees, were not an adequate substitute for habeas review. In holding those procedures inadequate, the Court relied on numerous factors they found persuasive: the fact that many of the detainees had been seeking release for six years already, and that the detainees may be unable to present additional evidence in their favor due to the circumstances of their detention. As the Court explained, the laws and the Constitution are designed to survive and remain in force, even in extraordinary times. Liberty and security can be reconciled, said the Court, and in our system, they are reconciled within the framework of the law.

Now I'm going to step back and mention one more case involving detainees at Guantanamo Bay. In Boumediene, the Supreme Court decided the procedures established in the Military Commissions Act were not an adequate substitute for habeas corpus. There was a man named, I don't pronounce it right, probably, Huzaifa Parhat, who's a Chinese Muslim who had been held at Guantanamo Bay for more than six years. Parhat did not ask for a writ of habeas corpus. Instead, he applied for relief under the very provisions of that Military Commissions Act. And he believed that the evidence that he was not an enemy combatant was so strong that he was willing to seek the more limited review under the Military Commissions Act, in hopes that his claim could be dealt with more quickly. In two short weeks after the Supreme Court handed down in Boumediene v. Bush, the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals decided Mr. Parhat's case. Much of the evidence in the case was classified, and so the opinion that was released to the public was stripped of names and of identifying information. But the DC Circuit Court completely agreed with Mr. Parhat and ruled that he was not, in fact, an enemy combatant. In the materials that the court did release, they directed the government to either release Parhat or present more reliable evidence at an expedited tribunal. And since that case, a few more detainees have successfully challenged their enemy combatant designations.

Now, I think I can safely say that these decisions I've mentioned tonight

do reflect the Supreme Court's commitment to uphold civil rights while trying to strike that delicate balance between the power of the courts and that of the executive and legislative branches and as Congress and the President more forcefully asserted their authority as they did with the Military Commissions Act and other actions. The Supreme Court was in turn obliged, more clearly to draw the bounds of the Constitution guarantees of civil rights. And I think that tension built and culminated in the the medium case, which I mentioned, in which the court was forced to confront the combined power of the executive and legislative branches. Now constitutional guarantees having been reconfirmed, I think the tension has dissipated somewhat in the intervening time.

Two days after taking office, President Obama signed an executive order to close the military prison at Guantanamo Bay within a year. He ordered a review of all of the evidence collected against each Guantanamo Bay detainee. On the basis of this review, each so-called enemy combatant is to be either transferred to another country, criminally prosecuted in our civilian courts, or otherwise dealt with, pursuant to lawful means, consistent with national security and the interests of justice. According to the order, the Secretary of State was ordered to take diplomatic measures to secure their transfer to their own country or another nation. The Department of Defense was ordered to suspend all military commissions pending the outcome of this review process.

In a memorandum signed the same day as the executive order, President Obama also called for a similar review of the status of Ali Saleh Kahlah al-Marri. Now al-Marri's case was significant because he was at that time the only person being held as an enemy combatant within the borders of the United States. He was held at the Navy brig in South Carolina. Alan Murray is a national cutter, and a lawful permanent resident of the United States. He was living in Peoria, Illinois with his family when he was taken into custody in 2001 by the FBI on suspicion of his being a sleeper al Qaeda agent who was conspiring to commit acts of terror against our country. He was subsequently designated an enemy combatant and sent the brig in South Carolina. And al-Marri challenged the President's authority to indefinitely detain a lawful permanent resident of the United States in a military prison. He challenged the constitutional adequacy of the procedures he was afforded to contest that determination.

Now in a very badly fractured opinion, The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit concluded that the President had the authority to detain al-Marri, but that he was not given a fair opportunity to contest his enemy combatant designation.

Al-Marri asked the US Supreme Court to review that decision. And in December, the Court agreed to hear his case. So I guess we'll all be reading more about that one.

Now, al-Marri has been transferred to a civilian prison and is awaiting prosecution in a civilian court. But the US Supreme Court in the meantime dismissed his challenge to the President's wartime authority. And it looks like the resolution of that issue is going to wait for another day, until such time as one of our presidents again wants to indefinitely detain a lawful permanent resident, like al-Marri.

So we have seen a remarkable set of cases dealing with the wartime power of the President and Congress. And the Supreme Court, I think, has provided a renewed commitment to civil liberties. And we have a new president's changes in policy that are taking place against the backdrop of these issues. So, as it was in the second half of the 20th century after World War Two, our nation's courts were called upon to consider human rights issues, even as the world and we struggle to respond to terrorism and brutality. And our courts and our branches of government have really addressed, in so many ways, their respective obligations. I think we can take some pride in the actions that were taken by the different branches of government and the respect shown to each. And although all the issues aren't resolved, I think that we can feel somewhat confident that our Constitutional guarantees are still significant and respected, and that the courts are hearing the issues as they're presented.

And I appreciate the chance to tell you that very long story today. Because I think it's one that the American people need to hear and understand and consider, and express your own views on what our nation should be doing. I'm going to open it up now to some questions from the audience. You're free to ask them, I may not answer them, but you're free to ask. And I think we have a few microphones back there. And perhaps you can make those available, and people can come forward with a microphone if they have a question. And we'll see how we progress.

Audience Member

Justice O'Connor, curious, how much does the oral argument in front of the Supreme Court really affect the ultimate decisions that are made? And number two, who is the better skier, you or Mac Parker?

Sandra Day O'Connor

Oh, he's much better than I am. But oral argument at the Court is not decisive in very many cases, because the parties file their argument in written form called briefs. And they aren't brief at all, they are long written arguments. And other interested parties are allowed to file "friend of the court" briefs. And most of what we learn in the cases we learn from all that briefing that goes on. We learn something at the oral argument, but it's used mostly by the justices, many of whom are former law professors, to ask a bunch of questions, and not to listen as intently. So, I don't think that oral arguments are decisive in many cases, but I've been there w