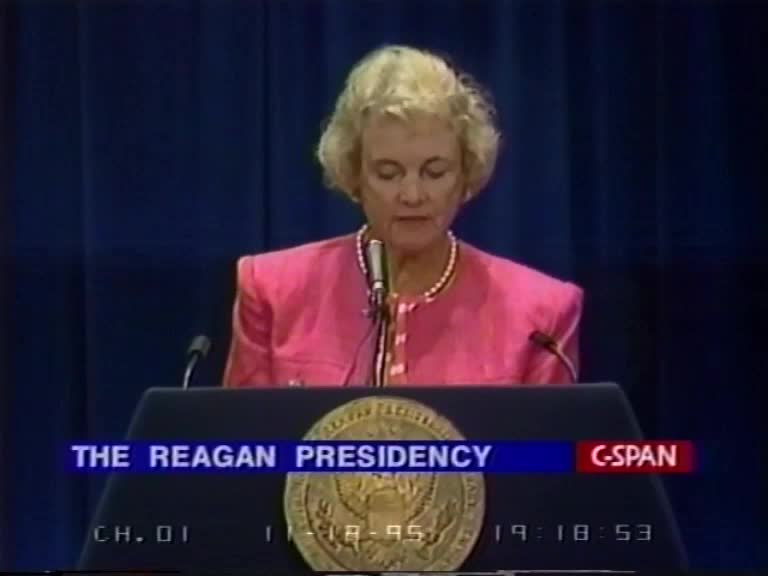

Sandra Day O'Connor

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Sandra Day O'Connor

Now, please sit. It's too hot to stand up. This is the first time that john and i have been privileged to visit the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. And it's such a treat to be here today and to see this wonderful spot, the building and a bit of the program that is displayed here. I'm very excited about it. It's simply lovely. And I'm sure it's no surprise, if I say that as President Reagan's first appointment to the Senate Supreme Court. The invitation to speak at his library was one that I very happily accepted. President Reagan instilled in this country of fresh pride in the principles that underlie our democratic system. He has always been a great champion of democracy. And as president he spoke often and forcefully about implementing our framers vision. He also pursued a vigorous and a successful foreign policy. Ronald Reagan held this country together through the last days of the Cold War. Through his resolute leadership, he paved the way for the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. It is only fitting that a man of such great accomplishment should have this wonderful facility dedicated to the study of his legacy. scholars will no doubt come here to debate the significance of the Reagan era era for years to come. But at least in one respect, Ronald Reagan's legacy is a more immediate significance.

One of the greatest opportunities that our president has to guide the future of the nation is through appointments to the federal bench, more than any other president in recent memory, Ronald, full advantage of this opportunity. His efforts in reshaping the federal judiciary are a great practical significance in this country, and have significant symbolic significance for emerging democracies throughout the world. In sheer numbers alone, the impact of Ronald Reagan's appointments on the landscape of our federal judiciary is immense. When he took office in January 1981, there were 90 vacancies on the federal bench. Halfway through his tenure on Office, Congress created another 85 judgeships. With these vacancies and those created by attrition, President Reagan appointed 379 federal judges, among them 292 District Court judges 83 Court of Appeals judges and three supreme court justices. One of them, of course, Justice Kennedy from this state. In his two times in office, President Reagan appointed more article three judges than any president in recent history 100 more than Jimmy Carter or Richard Nixon, and almost twice as many as other multi term presidents such as Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower or Harry Truman, when he left the White House in 1989, President Reagan had appointed almost half the sitting federal judges in this country.

But numbers tell only part of the story. President Reagan hill to the view that ours is a federal system, and that along with the separation of powers of the three branches of government, the Constitution scheme of the federal government is one of limited powers. And he thought this was an important bulwark against government access. For this reason, President Reagan advocated fidelity to the duties assigned to the various branches of the federal government under the Constitution and deference to the policy making authority of state governments. the republican party platform on which President Reagan was elected, called for, quote the appointment of judges who have the highest regard for protecting the rights of law abiding set.

And it will help views consistent with the belief in the decentralization of the federal government, and efforts to return decision making power to state and local officials in adhering to this platform, Ronald Reagan reaffirm that traditional role of the judiciary in this country and the vision of the framers of the Constitution, who carved out a narrow but important task for the judiciary, one which has only grown more prestigious over time. The framers were inspired in part by the writings of Baron Montesquieu, who said of the separation of powers, that there is no Liberty if the judiciary power is not separated from the legislative and executive. This principle has always been reflected in the operation of our federal judiciary, but never more vigorously than during the Reagan era. insulated from the workaday problems that plague gets coordinate branches, and invested with the authority and independence to judge the constitutionality of legislative and executive action alike. The judiciary serves a vital role in ensuring the proper functioning of our government.

Alexander Hamilton said of the judiciary, that it's the weakest of the three branches, because it has neither force nor will but merely judgment. Today, we recognize that this weakness is also the judiciary's greatest strength. Our federal judges are asked day in and day out, to exercise their judgment to review federal and state legislation. for consistency with the Constitution and the laws of the United States. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights limit the power of federal government, and grant rights to individual citizens. It's the job of our federal judiciary to ensure that this concept is maintained. Consequently, the power that federal judges wield is enormous. A single judge at any level in our unified judiciary, can declare an act of Congress invalid can enjoin the enforcement of a state statute or order a prisoner freed. judicial review no less than public accountability at the ballot box of elected officials, has proven to be an important check on extra legal action by the political branches of both the state and the federal government. As Montesqieu predicted, the judiciary is essential to the protection of our individual liberty. But independence and power also carried away with the possibility of abuse. The temptation to use the judicial office to advance social or political goals, instead of deciding cases on the basis of facts and law. James Madison spoke of this problem and the Federalist Papers when he said that power is of an encroaching nature, and that the mere demarcation on parchment of the constitutional limits of the several departments is not a sufficient guard against the tyrannical concentration of all the powers of government in the same hands.

This is a risk for the judiciary, just as it is for the executive branch. A tyrannical Supreme Court would hardly be more desirable than our tyrannical presidency. The vitality of our constitutional scheme has therefore depended on the animated attention of government officials to maintaining the separation of powers. But the framers devised very limited mechanisms through which the elected branches could curb judicial access. The legislature can only control the judiciary through the most unwieldy of instruments, the impeachment power, that power can only be used and narrow circumstances. And then because it's so draconian, it hasn't often been employed.

The president in turn, has an equally unwieldy tool with which to check judicial access, the power to appoint with senate approval, the men and women who sit on the federal bench. The appointment power is of course exercised more frequently than the impeachment power, but it's hardly a more precise instrument of control. To borrow from military parlance, it's more like a ballistic missile, then a smart bomb. Once they are confirmed and placed on the bench, federal judges have wide latitude and autonomy, and there is little let the elected branches can do to influence their conduct. After all, President Reagan has left the oval office that you see displayed here in this library. But I'm still in my chambers, doing my job, and the job of maintaining the proper allocation of authority to the federal judiciary, as a result falls in large measure on the federal judges themselves, whose restraint serves as a Bible check against the unwanted accretion of power.

President Reagan recognized this and he took pains to ensure that he exercised his appointment power wisely. He made Judicial Appointments a priority. He thought judges who would vigorously exercise the independent judgment that is the hallmark of our federal judiciary, but who would also wield their power responsibly. He attempted to appoint judges who were committed to a philosophy of restraint in the interpretation of the Constitution, who appreciate the importance of maintaining the separation of powers, and who leave to the other branches of government, the tasks assigned to them by the Constitution. It's tempting in assessing the impact of President Reagan's appointments strategy, to chart the record of the judges he's appointed, and to draw conclusions about the success with which he ensured that opinions issuing from the federal bench would reflect his ideological perspective. Some scholars have taken this approach, calculating for instance, the number of times that Reagan appointees and Carter appointees have voted together in criminal cases on the bench. But this sort of vote counting is deceptive. And in my view, rather fruitless.

I suggest there is a broader impact of the Reagan approach that we can chart and trace internationally. President Reagan's concepts of the way we think about government, and the the immediacy of our constitution came off suspiciously at a time when countries around the world began embracing the democratic ideals that President Reagan and others in this country hold so dear. Today, the emerging democracies in Eastern Europe and in the former Soviet Union, are redefining institutions of government and are struggling to implement democratic reform. Ronald Reagan was instrumental at a crucial time in exposing these nations to the American constitutional ideals, including the concept of judicial judgment and restraint, and a judiciary that could serve as a model of a strong but responsible third branch of government.

Of course, the new democracies in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union are not simply remaking themselves in our image. The process is far too complicated for that. But they're looking westward for ideas and advice. And they're grappling with many of the same problems that the framers of our own constitution faced, which powers to allocate to local government, and which vest in a central regime, how to allocate authority among the legislative, executive and judicial branches, how best to guarantee the robust protection of individual liberty. These issues are at the forefront of the ongoing debate over the allocation of power within the European Union, as well. As independent nations give up some of their autonomy to a larger unified regional or national government. They face the task of integrating their political and judicial systems, while at the same time maintaining their own national identities.

As was the case in this country, one of the principal hurdles that these emerging democracies face is in developing a strong and independent judiciary, we often take for granted the important roles that our own judiciary has played in shaping the history of the nation, in ensuring our individual liberties, and and maintaining the rule of law, free from political control, and imbued with the power of judicial review. Our judiciary has exerted a powerful influence over social and political life. But in the socialist regimes of Eastern Europe, there's little precedent for the vigorous protection of individual rights by the judiciary, and still less precedent for the exercise of judicial review. The notion that an unelected autonomous judiciary should have the power to strike down party sponsored legislation, and that it could actually exercise that power, is completely new. We have a 200 year history of studying federalism issues, notions of constitutionally mandated separation of powers. Because of this long experience, we have a special responsibility, I think, to help implement democratic reform in Eastern Europe and in the former Soviet Union, and particularly, to help in the development of strong independent judiciary's. They're, much of the systems we've been providing to the emerging democracies and Eastern Europe has come from private initiatives. The American Bar Association, for instance, launched the Central and Eastern European law initiative, which is known by the acronym CEELI, whose mission in part is to track the development of the judicial system, and the emerging democracies and to provide a systems where it's needed. I've been very active in that effort. And there's an impressive way of a systems by our United States government being offered in most of the developing democracies at all levels.

And this kind of interaction that we're having today, with these newly forming countries, is the continuation of a long tradition of political dialogue between Europe and America. The framers of our constitution were well versed in the writings of john Locke, Baron, Montesquieu, and other European students of political philosophy. And the structure of our government owes much to these great thinkers from Europe. In turn, Europeans have from time to time, looked at what the American framers wrote in crafting their own system of government. At no time in history, has this dialogue been more fervent? these emerging democracies of Eastern Europe and beyond are casting off the trappings of communism, and are adopting the ideological underpinnings of democratic forms of government. They're starting largely from scratch however, and as any student of American history knows, this process is not easy.

We took one bold step here, with our Articles of Confederation, before settling upon the division of authority laid out in our Constitution. To this day, we have to grapple with fundamental questions concerning the distribution of power within government. The same is true in Eastern Europe, democracy and the principle of self determination have taken root there quickly. But the first steps toward change have been awkward. These countries have only recently emerged from the pall of totality Attarian regimes, they struggled under the yoke of communism for a half century. And the reforms they're undertaking are unprecedented, we should expect to see some transitional difficulties. As we contemplate the situation in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, and chart the development of an independent judiciary in countries previously dominated by totalitarian regimes. We should be thankful for what we have and proud of what we have to offer. During the presidency of Ronald Reagan, we witness the resurgence of one of the longest running and most important debates in American political history. The national debate over the proper function of the federal judiciary, George Washington morn in his farewell address that even on a democracy side hours, the government must be vigilant and maintaining a firm separation of powers.

And we have only maintained the careful balance our founders envisioned by paying close heed to that morning. in Eastern Europe under communism, such an encroachment and the resulting despotism have always been the norm. The countries that the former Soviet bloc generally viewed their constitutions as being primarily symbolic. In theory, they defined principles according to which the state was morally and politically bound, and reserved certain individual rights is inviolable. But in practice, these documents these constitutions were not enforceable against the government. The Constitution might have guaranteed the right to free speech, for instance, but it's set up nobody procedure for ensuring that the state would not infringe upon that right whenever it was expedient to do so. Thus, there was no real protection of individual rights, and no, we'll check on government access, because there was no recourse to the courts. Under Polish law, for example, the judiciary was extensively independent, but judges were required to be party members, and political considerations influenced everything from case assignments, to decisions and individual cases.

The Soviet constitution of 1936 boldly announced that judges are independent and subject only to law. But like other institutions of government, the judiciary was controlled by the Communist Party. Similarly, in Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and other former Soviet satellite nations. The judiciary was in theory independent, falling practice, it was merely another instrument of the state. Consequently, as dissidents in these regimes repeatedly pointed out, there's always been a deep chasm between the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of citizens and the degree to which those freedoms were actually protected. The transition from communism to democracy and the rule of law should change all that recognizing the bedrock principle that there can be no Liberty without some provision for judicial oversight. One of the first things that the emerging democracies and Eastern Europe have done is to try to establish independent judiciary's, in some cases, it was the very first thing a new government did. For instance, the Hungarian Constitutional Court was the first institution created by the new Hungarian constitution for months even before parliamentary elections were held. Similarly, in Russia, President yeltsin said about restructuring the legal system to afford greater autonomy and power to Soviet judges, even before he addressed economic reforms. Consequently, the judicial branch there has been playing an instrumental role in easing the transition to democracy, a role that has in many respects been far more political, than those familiar with our judicial system, would suppose, is appropriate.

Because of the close contact between Eastern Europe and the democracies of the European Union, and because most of these emerging democracies walk in the future to become a part of the European Union, most of the new democracies in Eastern Europe have drawn more heavily on the political and judicial experience of their close neighbors in Europe, and less directly on the structure of the United States Constitution. As a result, their institutions don't look exactly like ours, even though the basic structure of government is similar. And these differences are nowhere more evident than in the structure of the judiciary, and our system. All questions of individual rights and all challenges to government action, are brought before a unified federal judiciary and a single judge within the system, state or federal, has the authority to apply the constitution and resolving that particular case.

The European model, by contrast, calls for splintering judicial duties. There are courts of general jurisdiction. But there is only one Constitutional Court in most of these countries that has the power of judicial review. the jurisdiction of such a Constitutional Court, moreover, is not like our court in several remarkable respects. Often, the Constitutional Court can be asked to render advisory opinions on the constitutionality of proposed legislation, upon request of either the executive or the legislative branch. If a lower court in these countries, and counters an issue that requires an interpretation of the Constitution, it has to stay all proceedings, stop handling the case and refer the constitutional issue to the Constitutional Court. Now, the result of all of this is that the constitutional courts in these emerging democratic countries swamped with cases, most of which raise fundamental questions about the division of authority within the government, the legality of executive action taken in response to an emergency, or the constitutionality of legislation. They're also facing, as did our court in its infancy, questions of their own jurisdiction, questions that may define the role of their court for years to come.

Our Supreme Court faced these questions over the course of several decades. And today, constitutional issues coming to our supreme court take years to percolate through the lower courts before being presented to our court. But because of their unusual jurisdiction, the constitutional courts that have been set up in Eastern Europe have had to address such issues within a very short span of time, and without the benefit of a percolation in lower courts. And this has placed the judiciary's in these countries, in a very real quandary. To establish their legitimacy, the constitutional courts have to justify their authority to a very skeptical public. But in asserting their independence, they also have to ignore public opinion. And neither task is proving to be easy. In these countries. The trend and many of them has been for elected officials to continue to exert influence over judicial proceedings. Old habits are hard to break. And many places the government has established the equivalent of a Ministry of Justice, whose function it is to own mercy that judiciary. And the transition to democracy has also meant a resolute adoption of the principle of majority rule. The people through their elected representatives are for the first time over there exerting real control over their government. And they don't want to let a judiciary overturn decisions of that majority. So we find that the judicial system in many of these countries is under real stress.

And many of the questions they're asked to address are highly political in nature. And these courts are running the risk of having their prestige and their autonomy and their authority undermined by the highly visible role. They have to play constitutional reform.

It's not our place, I think, to tell the judges of these constitutional courts and other countries, how to perform their duties. But because of our own experience, I do think Americans bear a special responsibility to join in the efforts to help create an independent non political judiciary in these emerging democracies, to the judges of Eastern Europe for whom the whole enterprise of judicial review is entirely new. The operation of our judiciary can be enlightening. Even if the parallels between our judicial systems are not exempt. As President Reagan repeatedly stressed and explaining his appointments to the federal bands, our judiciary draws its legitimacy from its role as the final interpreter an enforcer of the Constitution. through careful allegiance to the text of that document, it is the court has reserved for itself the luxury and the authority of engaging and non partisan autonomous interpretation on application of the law. Whatever else our judges can teach the Justices of constitutional courts, in newly forming democracies, they can demonstrate the role that I'm a tour and a season judiciary can play in the administration of government. This them, I think, is one of the legacies of the Reagan presidency. That is to provide a valuable example of a strong, stable and responsible judiciary for country throughout the world. Much of our world is in turmoil today, as political divisions are redrawn and as institutions of government are reshaped. The world is looking for models. And thanks in part, to Ronald Reagan's vision, I think we're able to offer some useful examples. Thanks for bearing with me tonight. And I'm told that we can use the balance of the time for questions from the floor. Dr. Smith, do you have any role to play in that regard?