Influences and Influence: Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and Constitutional Doctrine

Articles

INFLUENCES AND INFLUENCE: JUSTICE SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR AND CONSTITUTIONAL DOCTRINE

Kenneth M Murchison

INFLUENCES 392

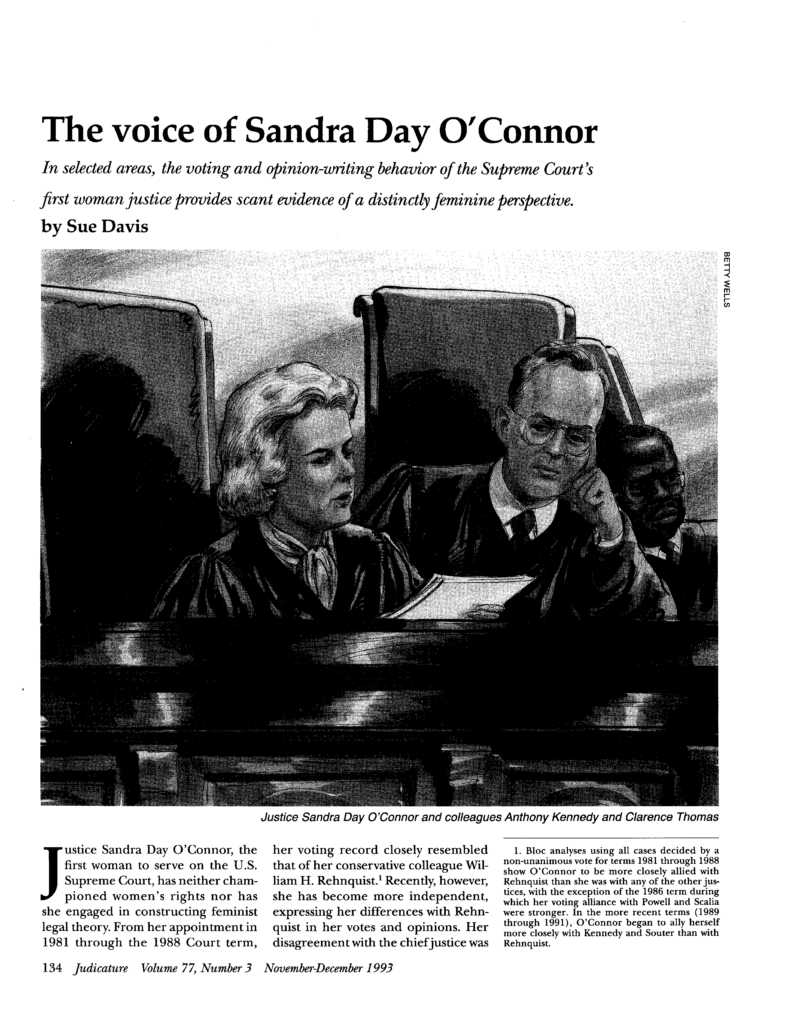

Gender: The First Female Justice 394

Politics: A Reagan Republican from the West 398

Legislative Experience: A Practical Politician 400

Religion: An Episcopalian 403

Judicial Experience: A State Court Judge 405

INFLUENCE AS A MEMBER OF THE COURT 410

Federalism 410

Separation of Powers 414

Individual Rights 417

Substantive Due Process 418

Equal Protection 421

Freedom of Religion 428

Freedom of Speech 434

Takings 444

Dissents: Failed Attempts to Influence 447

INFLUENCE ON THE FUTURE 452

CONCLUSION 460

Sandra Day O’Connor was both the first woman appointed to the United States Supreme Court and the first justice that President Ronald Regan appointed. She served for nearly a quarter century and earned a reputation as a centrist on a Court that was often closely divided. As a result, she was frequently a member of the Court’s majority in cases with narrow majorities, and her views often defined the reach and limits of the Court’s rulings.

391

This article offers an assessment of Justice O’Connor’s impact on constitutional doctrine from the perspective of a decade after her retirement. After a brief biographical summary, it describes how five factors-gender, legislative experience, religion, and judicial experience-influenced her judicial decisions. It then surveys her impact on constitutional doctrine while she was a member of the Court