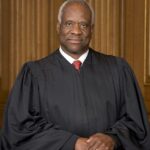

JUSTICE O'CONNOR announced the judgment of the Court and delivered an opinion, in which THE CHIEF JUSTICE, JUSTICE SCALIA, and JUSTICE THOMAS join.

In this case, the Court considers a challenge under the Due Process and Takings Clauses of the Constitution to the Coal

*Briefs of amici curiae urging reversal were filed for AlliedSignal Inc. et al. by Donald B. Ayer, Jonathan C. Rose, James E. Gauch, and Gregory G. Katsas; for Davon, Inc., by John W Fischer II; for Pardee & Curtin Lumber Co. et al. by Arthur Newbold, Ethan D. Fogel, and Andrew S. Miller; for Unity Real Estate Co. et al. by Robert H. Bork, David J. Laurent, Patrick M. McSweeney, William B. Ellis, and John L. Marshall; and for the Washington Legal Foundation by Timothy S. Bishop, Daniel

Briefs of amici curiae urging affirmance were filed for the Bituminous Coal Operators' Association, Inc., by Clifford M. Sloan and Paul L. Joffe; for California Cities and Counties et al. by John R. Calhoun, John D. Echeverria, James K. Hahn, Anthony Saul Alperin, Samuel L. Jackson, Joan R. Gallo, George Rios, Louise H. Renne, Gary T. Ragghianti, and S. Shane Stark; for Cedar Coal Co. et al. by David M. Cohen; for Freeman United Coal Mining Co. by Kathryn S. Matkov; for Ohio Valley Coal Co. et al. by John G. Roberts, Jr.; and for the United Mine Workers of America by Grant Crandall.

Briefs of amici curiae were filed for Midwest Motor Express, Inc., by Hervey H. Aitken, Jr., and Roy A. Sheetz; and for Pittston Co. by A. E. Dick Howard, Stephen M. Hodges, Wade W Massie, and Gregory B. Robertson. Industry Retiree Health Benefit Act of 1992 (Coal Act or Act), 26 U. S. C. §§ 9701-9722 (1994 ed. and Supp. II), which establishes a mechanism for funding health care benefits for retirees from the coal industry and their dependents. We conclude that the Coal Act, as applied to petitioner Eastern Enterprises, effects an unconstitutional taking.

I A

For a good part of this century, employers in the coal industry have been involved in negotiations with the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA or Union) regarding the provision of employee benefits to coal miners. When petitioner Eastern Enterprises (Eastern) was formed in 1929, coal operators provided health care to their employees through a prepayment system funded by payroll deductions. Because of the rural location of most mines, medical facilities were frequently substandard, and many of the medical professionals willing to work in mining areas were "company doctors," often selected by the coal operators for reasons other than their skills or training. The health care available to coal miners and their families was deficient in many respects. In addition, the cost of company-provided services, such as housing and medical care, often consumed the bulk of miners' compensation. See generally U. S. Dept. of Interior, Report of the Coal Mines Administration, A Medical Survey of the Bituminous-Coal Industry (1947) (Boone Report); Report of United States Coal Commission, S. Doc. No. 195, 68th Cong., 2d Sess. (1925).

In the late 1930's, the UMWA began to demand changes in the manner in which essential services were provided to miners, and by 1946, the subject of miners' health care had become a critical issue in collective bargaining negotiations between the Union and bituminous coal companies. When a breakdown in those negotiations resulted in a nationwide strike, President Truman issued an Executive order directing Secretary of the Interior Julius Krug to take possession of all bituminous coal mines and to negotiate "appropriate changes in the terms and conditions of employment" of miners with the UMW A. 11 Fed. Reg. 5593 (1946). A week of negotiations between Secretary Krug and UMW A President John L. Lewis produced the historic Krug-Lewis Agreement that ended the strike. See App. in No. 96-1947 (GAl), p. 610 (hereinafter App. (GAl)).

That agreement, described as "an almost complete victory for the miners," M. Fox, United We Stand 405 (1990), led to the creation of benefit funds, financed by royalties on coal produced and payroll deductions. The funds compensated miners and their dependents and survivors for wages lost due to disability, death, or retirement. The funds also provided for the medical expenses of miners and their dependents, with the precise benefits determined by UMWA-appointed trustees. In addition, the Krug-Lewis Agreement committed the Government to undertake a comprehensive survey of the living conditions in coal mining areas in order to assess the improvements necessary to bring those communities up to "recognized American standards." Krug-Lewis Agreement § 5, App. (GAl) 613. That study concluded that the medical needs of miners and their dependents would be more effectively served through "a broad prepayment system, based on sound actuarial principles." Boone Report 226-227.

Shortly after the study was issued, the mines returned to private control and the UMWA and several coal operators entered into the National Bituminous Goal Wage Agreement of 1947 (1947 NBGWA), App. (GAl) 615, which established the United Mine Workers of America Welfare and Retirement Fund (1947 W &R Fund), modeled after the KrugLewis benefit trusts. The Fund was to use the proceeds of a royalty on coal production to provide pension and medical benefits to miners and their families. The 1947 NBCWA did not specify the benefits to which miners and their dependents were entitled. Instead, three trustees appointed by the parties were given authority to determine "coverage and eligibility, priorities among classes of benefits, amounts of benefits, methods of providing or arranging for provisions for benefits, investment of trust funds, and all other related matters." 1947 NBCWA 146, App. (CA1) 619.

Disagreement over benefits continued, however, leading to the execution of another NBCWA in 1950, which created a new multiemployer trust, the United Mine Workers of America Welfare and Retirement Fund of 1950 (1950 W&R Fund). The 1950 W &R Fund established a 30-cents-per-ton royalty on coal produced, payable by signatory operators on a "several and not joint" basis for the duration of the 1950 Agreement. 1950 NBCWA 63, App. (CA1) 640. As with the 1947 W&R Fund, the 1950 W&R Fund was governed by three trustees chosen by the parties and vested with responsibility to determine the level of benefits. Id., at 59-61, App. (CA1) 638-639. Between 1950 and 1974, the 1950 NBCW A was amended on occasion, and new NBCW A's were adopted in 1968 and 1971. Except for increases in the amount of royalty payments, however, the terms and structure of the 1950 W &R Fund remained essentially unchanged. A 1951 amendment recognized the creation of the Bituminous Coal Operators' Association (BCOA), a multiemployer bargaining association, which became the primary representative of coal operators in negotiations with the Union. See App. (CA1) 647-648.

Under the 1950 W &R Fund, miners and their dependents were not promised specific benefits. As the 1950 W &R Fund's Annual Report for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1955, explained:"Under the legal and financial obligations… imposed [by the Trust Agreement], the Fund is operated on a pay-as-you-go basis, maintaining a sound relation ship between revenues and expenditures. Resolutions adopted by the Trustees governing Fund Benefits-Pensions, Hospital and Medical Care, and Widows and Survivors Benefits-specifically provide that all these Benefits are subject to termination, revision, or amendment, by the Trustees in their discretion at any time. No vested interest in the Fund extends to any beneficiary." Id., at 3-4, App. (CA1) 869-870.

See also Mine Workers Health and Retirement Funds v. Robinson, 455 U. S. 562, 565, and n. 2 (1982). Thus, the Fund operated using a fixed amount of royalties, with the trustees having the authority to establish and adjust the level of benefits provided so as to remain within the budgetary constraints.

Subsequent annual reports of the 1950 W &R Fund reiterated that benefits were subject to change. See, e. g., 1950 W&R Fund Annual Report for the Year Ending June 30, 1956 (1956 Annual Report), p. 30, App. (CA1) 929 ("Resolutions adopted by the Trustees governing Fund BenefitsPensions, Hospital and Medical Care, and Widows and Survivors Benefits-specifically provide that all these Benefits are subject to termination, revision, or amendment, by the Trustees in their discretion at any time"); 1950 W &R Fund Annual Report for the Year Ending June 30, 1958, pp. 20-21, App. (CA1) 955-956 ("Trustee regulations governing Benefits specifically provide that all Benefits which have been authorized are subject to termination, suspension, revision, or amendment by the Trustees in their discretion at any time. Each beneficiary is officially notified of this governing provision at the time his Benefit is authorized").l Thus, although persons involved in the coal industry may have made occasional statements intimating that the 1950 W &R Fund promised lifetime health benefits, see App. (CA1) 1899, 1971-1972, it is clear that the 1950 W &R Fund did not, by its terms, guarantee lifetime health benefits for retirees and their dependents. In fact, as to widows of miners, the 1950 W &R Fund expressly limited health benefits to the time period during which widows would also receive death benefits. See, e. g., Robinson, supra, at 565-566; 1956 Annual Report 14, App. (CA1) 913.

Between 1950 and 1974, the trustees often exercised their prerogative to alter the level of benefits according to the Fund's budget. In 1960, for instance, "[t]he Trustees of the Fund, recognizing their legal and fiscal obligation to soundly administer the Trust Fund, took action prior to the close of the fiscal year, to curtail the excess of expenditures over income," by "limit[ing] or terminat[ing] eligibility for [certain] Trust Fund Benefits." 1960 Annual Report 2, App. (CA1) 1011. Similar concerns prompted the trustees to reduce monthly pension benefits by 25% at one point, and to limit the range of medical and pension benefits available to miners employed by operators who did not pay the required royalties. See 1961 Annual Report 2, 11-12, App. (CA1) 1044, 1053-1054; 1963 Annual Report 13, 16, App. (CA1) 1121, 1124.

Reductions in benefits were not always acceptable to the miners, and some wildcat strikes erupted in the 1960's. See Secretary of Labor's Advisory Commission on United Mine Workers of America Retiree Health Benefits, Coal Commission Report 22-23 (1990) (Coal Comm'n Report), App. (CA1)

1080; 1950 W &R Fund Annual Report for the Year Ending June 30, 1963 (1963 Annual Report), p. 5, App. (CA1) 1113; 1950 W &R Fund Annual Report for the Year Ending June 30, 1964, p. 8, App. (CA1) 1146; 1950 W &R Fund Annual Report for the Year Ending June 30, 1965, p. 18, App. (CA1) 1191; 1950 W&R Fund Annual Report for the Year Ending June 30, 1966 (1966 Annual Report), p. 19, App. (CA1) 1223. 1352-1353. Nonetheless, the 1950 W&R Fund continued to provide benefits on a "pay-as-you-go" basis, with the level of benefits fully subject to revision, until the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), 29 U. S. C. § 1001 et seq., introduced specific funding and vesting requirements for pension plans. To comply with ERISA, the UMWA and the BCOA entered into a new agreement, the 1974 NBCW A, which created four trusts, funded by royalties on coal production and premiums based on hours worked by miners, to replace the 1950 W&R Fund. See Robinson, supra, at 566. Two of the new trusts, the UMWA 1950 Benefit Plan and Trust (1950 Benefit Plan) and the UMW A 1974 Benefit Plan and Trust (1974 Benefit Plan), provided nonpension benefits, including medical benefits. Miners who retired before January 1, 1976, and their dependents were covered by the 1950 Benefit Plan, while active miners and those who retired after 1975 were covered by the 1974 Benefit Plan.

The 1974 NBCWA thus was the first agreement between the UMWA and the BCOA to expressly reference health benefits for retirees; prior agreements did not specifically mention retirees, and the scope of their benefits was left to the discretion of fund trustees. The 1974 NBCWA explained that it was amending previous medical benefits to provide a Health Services card for retired miners until their death, and to their widows until their death or remarriage. 1974 NBCWA 99, 105 (Summary of Principal Provisions, UMWA Health and Retirement Benefits), App. (CA1) 755, 758. Despite the expanded benefits, the 1974 NBCW A did not alter the employers' obligation to contribute only a fixed amount of royalties, nor did it extend employers' liability beyond the life of the agreement. See id., Art. XX, § (d), App. (CA1) 749.

As a result of the broadened coverage under the 1974 NBCW A, the number of eligible benefit recipients jumped dramatically. See 1977 Annual Report of the UMWA Wel fare and Retirement Funds 3, App. (CA1) 1253. A 1993 Report of the House Committee on Ways and Means explained:"The 1974 agreement was the first NBCW A to mention retiree health benefits. As part of a substantial liberalization of benefits and eligibility under both the pension and health plans, the 1974 contract provided lifetime health benefits for retirees, disabled mine workers, and spouses, and extended the benefits to surviving spouses…. " House Committee on Ways and Means, Financing UMW A Coal Miner "Orphan Retiree" Health Benefits, 103d Cong., 1st Sess., 4 (Comm. Print 1993) (House Report).

The increase in benefits, combined with various other circumstances-such as a decline in the amount of coal produced, the retirement of a generation of miners, and rapid escalation of health care costs-quickly resulted in financial problems for the 1950 and 1974 Benefit Plans. In response, the next NBCW A, executed in 1978, assigned responsibility to signatory employers for the health care of their own active and retired employees. See 1978 NBCWA, Art. XX, § (c)(3), App. (CA1) 778. The 1974 Benefit Plan remained in effect, but only to cover retirees whose former employers were no longer in business.

To ensure the Benefit Plans' solvency, the 1978 NBCWA included a "guarantee" clause obligating signatories to make sufficient contributions to maintain benefits during that agreement, and "evergreen" clauses were incorporated into the Benefit Plans so that signatories would be required to contribute as long as they remained in the coal business, regardless of whether they signed a subsequent agreement. See id., § (h), App. (CA1) 787-788; House Report 5. As a result, the coal operators' liability to the Benefit Plans shifted from a defined contribution obligation, under which employers were responsible only for a predetermined amount of royalties, to a form of defined benefit obligation, under which employers were to fund specific benefits.

Despite the 1978 changes, the Benefit Plans continued to suffer financially as costs increased and employers who had signed the 1978 NBCW A withdrew from the agreement, either to continue in business with nonunion employees or to exit the coal business altogether. As more and more coal operators abandoned the Benefit Plans, the remaining signatories were forced to absorb the increasing cost of covering retirees left behind by exiting employers. A spiral soon developed, with the rising cost of participation leading more employers to withdraw from the Benefit Plans, resulting in more onerous obligations for those that remained. In 1988, the UMWA and BCOA attempted to relieve the situation by imposing withdrawal liability on NBCW A signatories who seceded from the Benefit Plans. See 1988 NBCW A, Art. XX, §§ (i) and (j), App. (CA1) 805, 828-829. Even so, by 1990, the 1950 and 1974 Benefit Plans had incurred a deficit of about $110 million, and obligations to beneficiaries were continuing to surpass revenues. See House Report 9; Coal Comm'n Report 43-44, App. (CA1) 1373-1374.

B

In response to unrest among miners, such as the lengthy strike that followed Pittston Coal Company's refusal to sign the 1988 NBCWA, Secretary of Labor Elizabeth Dole announced the creation of the Advisory Commission on United Mine Workers of America Retiree Health Benefits (Coal Commission or Commission). The Coal Commission was charged with "recommend[ing] a solution for ensuring that orphan retirees in the 1950 and 1974 Benefit Trusts will continue to receive promised medical care." Coal Comm'n Report 2, App. (CA1) 1333. The Commission explained that "[h]ealth care benefits are an emotional subject in the coal industry, not only because coal miners have been promised and guaranteed health care benefits for life, but also because coal miners in their labor contracts have traded lower pensions over the years for better health care benefits." Coal Comm'n Report, Executive Summary vii, App. (CA1) 1324. The Commission agreed that "a statutory obligation to contribute to the plans should be imposed on current and former signatories to the [NBCWA]," but disagreed about "whether the entire [coal] industry should contribute to the resolution of the problem of orphan retirees." Id., at vii-viii, App. (CA1) 1324-1325. Therefore, the Commission proposed two alternative funding plans for Congress' consideration.

First, the Commission recommended that Congress establish a fund financed by an industrywide fee to provide health care to orphan retirees at the level of benefits they were entitled to receive at that fund's inception. To cover the cost of medical benefits for retirees from signatories to the 1978 or subsequent NBCWA's who remained in the coal business, the Commission proposed the creation of another fund financed by the retirees' most recent employers. Id., at 61, App. (CA1) 1390. The Commission also recommended that Congress codify the "evergreen" obligation of the 1978 and subsequent NBCWA's. Id., at 63, App. (CA1) 1392.

As an alternative to imposing industrywide liability, the Commission suggested that Congress spread the cost of retirees' health benefits across "a broadened base of current and past signatories to the contracts," apparently referring to the 1978 and subsequent NBCW A's. See id., at 58, 65, App. (CA1) 1387, 1394. Not all Commission members agreed, however, that it would be fair to assign such a burden to signatories of the 1978 agreement. Four Commissioners explained that "[i]ssues of elemental fairness are involved" in imposing obligations on "respectable operators who made decisions in the past to move to different locales, invest in different technology, or pursue their business with or without respect to union presence." Id., at 85, App. (CA1) 1414 (statement of Commissioners Michael J. Mahoney, Carl J. Schramm, Arlene Holen, Richard M. Holsten); see also id., at 81-82, App. (CA1) 1410-1411 (statement of Commissioner Richard M. Holsten).

After the Coal Commission issued its report, Congress considered several proposals to fund health benefits for UMWA retirees. At a 1991 hearing, a Senate subcommittee was advised that more than 120,000 retirees might not receive "the benefits they were promised." Coal Commission Report on Health Benefits of Retired Coal Miners: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Medicare and Long-Term Care of the Senate Committee on Finance, 102d Cong., 1st Sess., 45 (1991) (statement of BCOA Chairman Michael K. Reilly). The Coal Commission's Chairman submitted a statement urging that Congress' assistance was needed "to fulfill the promises that began in the collective bargaining process nearly 50 years ago…. " Id., at 306 (prepared statement of W. J. Usery, Jr.). Some Senators expressed similar concerns that retired miners might not receive the benefits promised to them. See id., at 16 (statement of Sen. Dave Durenberger) (describing issue as involving "a whole bunch of promises made to a whole lot of people back in the 1940s and 1950s when the cost consequences of those problems were totally unknown"); id., at 59 (prepared statement of Sen. Orrin G. Hatch) (stating that "miners and their families… were led to believe by their own union leaders and the companies for which they worked that they were guaranteed lifetime [health] benefits").

In 1992, as part of a larger bill, both Houses passed legislation based on the Coal Commission's first proposal, which required signatories to the 1978 or any subsequent NBCW A to fund their own retirees' health care costs and provided for orphan retirees' benefits through a tax on future coal production. See H. R. Conf. Rep. No. 102-461, pp. 268-295 (1992). President Bush, however, vetoed the entire bill. See H. R. Doc. No. 102-206, p. 1 (1992). Congress responded by passing the Coal Act, a modified version of the Coal Commission's alternative funding plan. In the Act, Congress purported "to identify persons most responsible for [1950 and 1974 Benefit Plan] liabilities in order to stabilize plan funding and allow for the provision of health care benefits to… retirees." § 19142(a)(2), 106 Stat. 3037, note following 26 U. S. C. § 9701; see also 138 Congo Rec. 34001 (1992) (Conference Report on Coal Act) (explaining that, under the Coal Act, "those companies which employed the retirees in question, and thereby benefitted from their services, will be assigned responsibility for providing the health care benefits promised in their various collective bargaining agreements").

The Coal Act merged the 1950 and 1974 Benefit Plans into a new multiemployer plan called the United Mine Workers of America Combined Benefit Fund (Combined Fund). See 26 U. S. C. §§ 9702(a)(1), (2).2 The Combined Fund provides "substantially the same" health benefits to retirees and their dependents that they were receiving under the 1950 and 1974 Benefit Plans. See §§ 9703(b)(1), (f). It is financed by annual premiums assessed against "signatory coal operators," i. e., coal operators that signed any NBCWA or any other agreement requiring contributions to the 1950 or 1974 Benefit Plans. See §§ 9701(b)(1), (3); § 9701(c)(1). Any signatory operator who "conducts or derives revenue from any business activity, whether or not in the coal industry," may be liable for those premiums. §§ 9706(a), 9701(c)(7). Where a signatory is no longer involved in any business activity, premiums may be levied against "related person[s]," including successors in interest and businesses or corporations under common control. §§ 9706(a), 9701(c)(2)(A).

The Commissioner of Social Security (Commissioner) calculates the premiums due from any signatory operator based

2The Coal Act also established another fund, the 1992 UMWA Benefit Plan, which is not at issue here. See 26 U. S. C. § 9712. on the following formula, by which retirees are assigned to particular operators:"For purposes of this chapter, the Commissioner of Social Security shall… assign each coal industry retiree who is an eligible beneficiary to a signatory operator which (or any related person with respect to which) remains in business in the following order:

"(1) First, to the signatory operator which"(A) was a signatory to the 1978 coal wage agreement or any subsequent coal wage agreement, and"(B) was the most recent signatory operator to employ the coal industry retiree in the coal industry for at least 2 years."(2) Second, if the retiree is not assigned under paragraph (1), to the signatory operator which"(A) was a signatory to the 1978 coal wage agreement or any subsequent coal wage agreement, and"(B) was the most recent signatory operator to employ the coal industry retiree in the coal industry."(3) Third, if the retiree is not assigned under paragraph (1) or (2), to the signatory operator which employed the coal industry retiree in the coal industry for a longer period of time than any other signatory operator prior to the effective date of the 1978 coal wage agreement." § 9706(a).

It is the application of the third prong of the allocation formula, § 9706(a)(3), to Eastern that we review in this case.3 II A

Eastern was organized as a Massachusetts business trust in 1929, under the name Eastern Gas and Fuel Associates. Its current holdings include Boston Gas Company and a barge operator. Therefore, although Eastern is no longer involved in the coal industry, it is "in business" within the meaning of the Coal Act. Until 1965, Eastern conducted extensive coal mining operations centered in West Virginia and Pennsylvania. As a signatory to each NBCWA executed between 1947 and 1964, Eastern made contributions of over $60 million to the 1947 and 1950 W&R Funds. Brief for Petitioner 6.

In 1963, Eastern decided to transfer its coal-related operations to a subsidiary, Eastern Associated Coal Corp. (EACC). The transfer was completed by the end of 1965, and was described in Eastern's federal income tax return as an agreement by EACC to assume all of Eastern's liabilities arising out of coal mining and marketing operations in exchange for Eastern's receipt of EACC's stock. EACC made similar representations in Security and Exchange Commission filings, describing itself as the successor to Eastern's coal business. See App. (CA1) 117-118. At that time, the 1950 W&R Fund had a positive balance of over $145 million. 1966 Annual Report 3, App. (CA1) 1207.

Eastern retained its stock interest in EACC through a subsidiary corporation, Coal Properties Corp. (CPC), until 1987, and it received dividends of more than $100 million from EACC during that period. See Brief for Petitioner 6, n. 13. In 1987, Eastern sold its interest in CPC to respondent Peabody Holding Company, Inc. (Peabody). Under the terms of the agreement effecting the transfer, Peabody, CPC, and EACC assumed responsibility for payments to certain benefit plans, including the "Benefit Plan for UMW A Represented Employees of EACC and Subs." App. 206a, 210a. As of June 30,1987, the 1950 and 1974 Benefit Plans reported surplus assets, totaling over $33 million. House Report 9.

B

Following enactment of the Coal Act, the Commissioner assigned to Eastern the obligation for Combined Fund premiums respecting over 1,000 retired miners who had worked for the company before 1966, based on Eastern's status as the pre-1978 signatory operator for whom the miners had worked for the longest period of time. See 26 U. S. C. § 9706(a). Eastern's premium for a 12-month period exceeded $5 million. See Brief for Petitioner 16.

Eastern responded by suing the Commissioner, as well as the Combined Fund and its trustees, in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts. Eastern asserted that the Coal Act, either on its face or as applied, violates substantive due process and constitutes a taking of its property in violation of the Fifth Amendment. Eastern also challenged the Commissioner's interpretation of the Coal Act. The District Court granted summary judgment for respondents on all claims, upholding both the Commissioner's interpretation of the Coal Act and the Act's constitutionality. Eastern Enterprises v. Shalala, 942 F. Supp. 684 (Mass. 1996).

The Court of Appeals for the First Circuit affirmed.

Eastern Enterprises v. Chater, 110 F.3d 150 (1997). The court rejected Eastern's challenge to the Commissioner's interpretation of the Coal Act. Addressing Eastern's substantive due process claim, the court described the Coal Act as "entitled to the most deferential level of judicial scrutiny," explaining that, "[w]here, as here, a piece of legislation is purely economic and does not abridge fundamental rights, a challenger must show that the legislature acted in an arbitrary and irrational way." Id., at 155-156 (internal quotation marks omitted). In the court's view, the retroactive liability imposed by the Act was permissible "[a]s long as the retroactive application… is supported by a legitimate legislative purpose furthered by rational means," for "judgments about the wisdom of such legislation remain within the exclusive province of the legislative and executive branches." I d., at 156 (internal quotation marks omitted). The court concluded that Congress' purpose in enacting the Coal Act was legitimate and that Eastern's obligations under the Act are rationally related to those objectives, because Eastern's execution of pre-1974 NBCWA's contributed to miners' expectations of lifetime health benefits. Id., at 157. The court rejected Eastern's argument that costs of retiree health benefits should be borne by post-1974 coal operators, reasoning that Eastern's proposal would require coal operators to fund health benefits for miners whom the operators had never employed. I d., at 158, n. 5. The court also noted the substantial dividends that Eastern had received from EACC. Id., at 158.

The court analyzed Eastern's claim that the Coal Act effects an uncompensated taking under the three factors set out in Connolly v. Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, 475 U. S. 211, 225 (1986): "(1) the economic impact of the regulation on the claimant, (2) the extent to which the regulation interferes with the claimant's reasonable investmentbacked expectations, and (3) the nature of the governmental action." 110 F. 3d, at 160. With respect to the Act's economic impact on Eastern, the court observed that the Act "does not involve the total deprivation of an asset." Ibid. The Act's terms, the court found, "reflec[t] a sufficient degree of proportionality" because Eastern is assigned liability only for miners "whom it employed for a relevant (and relatively long) period of time," and then only if no post-1977 NBCWA signatory (or related person) can be found. Ibid. The court also rejected Eastern's contention that the Act unreasonably interferes with its investment-backed expectations, explaining that the pattern of federal intervention in the coal industry and Eastern's role in fostering an expectation of lifetime health benefits meant that Eastern "had every reason to anticipate that it might be called upon to bear some of the financial burden that this expectation engendered." Id., at 161. Finally, in assessing the nature of the challenged governmental action, the court determined that the Coal Act does not result in the physical invasion or permanent appropriation of Eastern's property, but merely "adjusts the benefits and burdens of economic life to promote the common good." Ibid. (internal quotation marks omitted). The court also noted that the premiums are disbursed to the privately operated Combined Fund, not to a government entity. For those reasons, the court concluded, "there is no basis whatever for [Eastern's] claim that the [Coal Act] transgresses the Takings Clause." Ibid.

Other Courts of Appeals have also upheld the Coal Act against constitutional challenges.4 In view of the importance of the issues raised in this case, we granted certiorari. 522 U. S. 931 (1997).

III

We begin with a threshold jurisdictional question, raised in the federal respondent's answer to Eastern's complaint:

Whether petitioner's takings claim was properly filed in Federal District Court rather than the United States Court of Federal Claims. See App. (CA1) 40. Although the Commissioner no longer challenges the Court's adjudication of this action, see Brief for Federal Respondent 38-39, n. 30, it is appropriate that we clarify the basis of our jurisdiction over petitioner's claims.

4See, e. g., Holland v. Keenan Trucking Co., 102 F.3d 736, 739-742 (CA4 1996); Lindsey Coal Mining Co. v. Chater, 90 F.3d 688, 693-695 (CA3 1996); In re Blue Diamond Coal Co