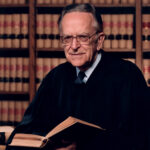

JUSTICE O'CONNOR, with whom JUSTICE BLACKMUN joins, dissenting.

By failing to interpret 18 U. S. C. § 5037(c)(1)(B) in light of the statutory scheme of which it is a part, the Court interprets a "technical amendment" to make sweeping changes to the process and focus of juvenile sentencing. Instead, the Court should honor Congress' clear intention to leave settled practice in juvenile sentencing undisturbed.

When Congress enacted the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, it authorized the United States Sentencing Commission (Sentencing Commission or Commission) to overhaul the discretionary system of adult sentencing. As an important aspect of this overhaul, Guidelines sentencing formalizes sentencing procedures. The Commission explains:"In pre-guidelines practice, factors relevant to sentencing were often determined in an informal fashion. The informality was to some extent explained by the fact that particular offense and offender characteristics rarely had a highly specific or required sentencing consequence. This situation will no longer exist under sentencing guidelines. The court's resolution of disputed sentencing factors will usually have a measurable effect on the applicable punishment. More formal ity is therefore unavoidable if the sentencing process is to be accurate and fair." United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual § 6A1.3, comment (Nov. 1991) (USSG).

Another significant change permits an appeal when the Guidelines are incorrectly applied or departed from, 18 U. S. C. § 3742; under prior law, a sentence within statutory limits was not generally subject to review, United States v. Tucker, 404 U. S. 443, 447 (1972). Thus, factual findings made at adult sentencing hearings can be challenged on appeal.

When Congress made these fundamental changes in sentencing, it repealed the Youth Corrections Act, Pub. L. 98473, Title II, § 218(a)(8), 98 Stat. 2027 (1984), which gave special treatment to defendants under 22. Congress did not, however, repeal the Juvenile Delinquency Act, which applies to defendants under 18, and clearly indicated that the Commission was only to study the feasibility of sentencing guidelines for juveniles, see 28 U. S. C. §§ 995(a)(1)-(a)(9), a process which is still in progress. Brief for United States 11, n. 1. Thus, Congress did not intend the Guidelines to apply to juveniles. Section 5037(c)(1)(B) must be interpreted against this backdrop.

Before the Sentencing Reform Act, § 5037(c)(1)(B) limited juvenile sentences by the correlative adult statutory maximum. As part of the Sentencing Reform Act, Congress made clear that this past practice would remain the same by limiting juvenile sentences to: "the maximum term of imprisonment that would be authorized by section 3581 (b) if the juvenile had been tried and convicted as an adult," 18 U. S. C. § 5037(c)(1)(B) (1982 ed., Supp. II) (emphasis added). The reference to § 3581(b), which classifies offenses and sets out maximum terms, clarified that the statutory maximum of the offense, not the Guideline maximum, would still limit the juvenile's sentence. Thus, consonant with its decision to leave juvenile sentencing in place, Congress did not change § 5037(c)(1)(B) to require sentencing judges in juvenile cases to calculate Guideline maximum sentences.

As the plurality acknowledges, ante, at 299-304, the crossreference to § 3581(b) added by the Sentencing Reform Act created a new ambiguity as to whether the maximum sentence referred to was that authorized in the particular offense statute, or in the offense classification statute. To resolve the ambiguity, the cross-reference was deleted in 1986 as one of numerous technical amendments. The Court reads this technical amendment as changing § 3581's reference from the statutory maximum to the Guideline maximum, even though before the amendment the statute clearly did not refer to the Guideline maximum. While the original version of § 5037(c)(1)(B) was ambiguous in other respects, there was never any question that § 5037(c)(1)(B) referred to the adult statutory maximum. There is no indication that Congress intended to change pre-existing practice. Section 5037(c) (l)(B), read in this context, still unambiguously refers to the statutory maximum. And because § 5037(c)(1)(B) is unambiguous in this respect, the rule of lenity does not apply here. Moskal v. United States, 498 U. S. 103, 108 (1990) (Court may look to structure of statute to ascertain the sense of a provision before resorting to rule of lenity). The Court, however, construes § 5037(c)(1)(B) to change pre-existing practice only by reading it in a vacuum apart from the rest of the Sentencing Reform Act, thus violating the canon of construction that "the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme." Davis v. Michigan Dept. of Treasury, 489 U. S. 803, 809 (1989).

The practical implications of the Court's reading demonstrate why its construction runs contrary to Congress' decision not to apply the Guidelines to juveniles. Requiring a district court to calculate a Guideline maximum for each juvenile imports formal factfinding procedures foreign to the discretionary sentencing system Congress intended to re tain. Juvenile proceedings, in contrast to adult proceedings, have traditionally aspired to be "intimate, informal [and] protective." McKeiver v. Pennsylvania, 403 U. S. 528, 545 (1971). One reason for the traditional informality of juvenile proceedings is that the focus of sentencing is on treatment, not punishment. The presumption is that juveniles are still teachable and not yet "hardened criminals." S. Rep. No. 1989, 75th Cong., 3d Sess., 1 (1938). See Mc Keiver, supra; 18 U. S. C. § 5039 ("Whenever possible, the Attorney General shall commit a juvenile to a foster home or community-based facility located in or near his home community"). As a result, the sentencing considerations relevant to juveniles are far different from those relevant to adults.

The Court asserts, naively it seems to me, that it is not requiring "plenary application" of the Guidelines, ante, at 307, and makes the process of determining the Guideline maximum seem easy-a court need only look at the offense the juvenile was found guilty of violating and his criminal history, ante, at 296. In practice, however, calculating a Guideline maximum is much more complicated. Even in this relatively straightforward case, respondent was said to have stolen the car he was driving. Although apparently not placed in issue at the sentencing hearing, that conduct might, if proven and connected to the offense of which respondent was convicted, enhance the applicable Guideline maximum as "relevant conduct." See USSG § 1B1.3. Respondent's role in the offense might also warrant an adjustment of the Guideline maximum. §§ 3B1.1, 3B1.2. The District Court made a determination that respondent had not accepted responsibility, and that finding changed the calculation of the Guideline maximum. Tr. 3 (Jan. 25, 1991), §3E1.1. The District Court also had to take into account factors not considered by the Guidelines in determining whether or not a departure was warranted, which would increase or decrease the "maximum" sentence by an undiscernible "reasonable" amount. Tr. 3-4, 18 U. S. C. § 3553(b). In short, the Guide line maximum is not static or readily ascertainable, but depends on particularized findings of fact and discretionary determinations made by the sentencing judge.

These determinations may even require adversarial evidentiary hearings. Yet such formal factual investigations are not provided for by the Juvenile Delinquency Act. There is no indication in the statute that the judge is required to support the sentence with particular findings. USSG § 6A1.3 and Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 32(a)(1), as amended after the Guidelines, do provide for an adversarial sentencing procedure for adults that accommodates Guideline factfinding. Rule 32 does not apply when it conflicts with provisions of the Juvenile Delinquency Act, however, see Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 54(b)(5), and it seems to me a serious question whether adversarial factfinding is what Congress had in mind for juvenile sentencing. An even more serious question is whether Congress intended juveniles to be able to appeal the findings of fact that determine the Guideline maximum. Yet the Court's decision would seem to require provision for such appeals.

In addition, a Guideline maximum for an adult incorporates factors the Sentencing Commission has found irrelevant to juvenile sentencing, see, e. g., USSG § 4B1.1 (career offender status inapplicable to defendants under 18), and does not incorporate factors Congress has found relevant to juvenile sentencing, see, e. g., USSG §§ 5H1.1, 5H1.6 (age and family ties irrelevant to Guideline sentencing). As a result, the Guideline maximum for an adult cannot serve as a useful point of comparison. In sum, the cumbersome process of determining a comparable Guideline maximum threatens to dominate the juvenile sentencing hearing at the expense of considerations more relevant to juveniles.

I cannot infer that Congress meant to overhaul and refocus the procedures of juvenile sentencing in such a fundamental way merely by deleting a cross-reference in a technical amendment, especially when Congress expressly left juve nile sentencing out of the scope of the Sentencing Reform Act and directed the Commission to examine how sentencing guidelines might be tailored to juveniles.

This case is admittedly unusual in that respondent was sentenced to a longer sentence than a similarly situated adult. Before the Guidelines were enacted, however, such anomalies were not unknown: A juvenile could receive a longer sentence than a similarly situated adult, as long as the sentence was within the statutory maximum. We should not try to address the disparity presented in this particular case by changing all juvenile sentencing in ways that Congress did not intend. Instead, we should wait for the Sentencing Commission and Congress to decide whether to fashion appropriate guidelines for juveniles. For this reason, I respectfully dissent.