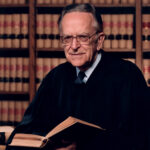

JUSTICE O'CONNOR, with whom JUSTICE BLACKMUN joins, concurring.

I join the Court's opinion and its judgment because I agree that this Court has appellate jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1252 and that the District Court abused its discretion in issuing a nationwide preliminary injunction against enforcement of the $10 fee limitation in 38 U.S.C. § 3404(c). I also agree that the record before us is insufficient to evaluate the claims of any individuals or identifiable groups. I write separately to note that such claims remain open on remand.

The grant of appellate jurisdiction under § 1252 does not give the Court license to depart from established standards of appellate review. This Court, like other appellate courts, has always applied the "abuse of discretion" standard on review of a preliminary injunction. See, e.g., Doran v. Salem Inn, Inc., 422 U. S. 922, 422 U. S. 931 -932 (1975). As the Court explains, direct appeal of a preliminary injunction under § 1252 is appropriate in the rare case, such as this, where a district court has issued a nationwide injunction that, in practical effect, invalidates a federal law. In such circumstances, § 1252 "assure[s] an expeditious means of affirming or removing the restraint on the Federal Government's administration of the law…." Heckler v. Edwards, 465 U. S. 870, 465 U. S. 882 (1984). See also id. at 465 U. S. 881, nn. 15 and 16 (§ 1252 is closely tied to the need to speedily resolve injunctions preventing the effectuation of Acts of Congress). Contrary to the suggestion of JUSTICE BRENNAN, post at 473 U. S. 355, the Court fully effectuates the purpose of § 1252 by vacating the preliminary injunction which the District Court improperly issued. Since the District Court did not reach the merits, any cloud on the constitutionality of the $10 fee limitation that remains after today's decision is no greater than exists prior to judgment on the merits in any proceeding questioning a statute's constitutionality.

A preliminary injunction is only appropriate where there is a demonstrated likelihood of success on the merits. Doran v. Salem Inn, Inc., supra.In order to justify the sort of categorical relief the District Court afforded here, the fee limitation must pose a risk of erroneous deprivation of rights in the generality of cases reached by the injunctive relief.Cf. Mathews v. Eldridge,424 U. S. 319,424 U. S. 344(1976). Given the nature of the typical claim and the simplified Veterans' Administration procedures, the record falls short of establishing any likelihood of such sweeping facial invalidity.Anteat473 U. S. 329-330.

As the Court observes, the record also "is… short on definition or quantification of complex' cases" which might constitute a "group" with respect to which the process provided is "[in]sufficient for the large majority." Ante at 473 U. S. 329, 473 U. S. 330 ; Parham v. J. R., 442 U. S. 584, 442 U. S. 617 (1979). The "determination of what process is due [may] var[y]" with regard to a group whose "situation differs" in important respects from the typical veterans' benefit claimant. Parham v. J. R., supra, at 442 U. S. 617. Appellees' claims, however, are not framed as a class action, nor were the lower court's findings and relief narrowly drawn to reach some discrete class of complex cases. In its present posture, this case affords no sound basis for carving out a subclass of complex claims that, by their nature, require expert assistance beyond the capabilities of service representatives to assure the veterans "`[a] hearing appropriate to the nature of the case.'" Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U. S. 371, 401 U. S. 378 (1971), quoting Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339 U. S. 306, 339 U. S. 313 (1950). Ante at 473 U. S. 329.

Nevertheless, it is my understanding that the Court, in reversing the lower court's preliminary injunction, does not determine the merits of the appellees' individual "as applied" claims. The complaint indicates that appellees challenged the fee limitation both on its face and as applied to them, and sought a ruling that they were entitled to a rehearing of claims processed without assistance of an attorney. I App. 39-42. Appellee Albert Maxwell, for example, alleges that his service representative retired and failed to notify him that he had dropped his case. Mr. Maxwell's records indicate that he suffers from the after effects of malaria contracted in the Bataan death march, as well as from multiple myelomas allegedly a result of exposure to radiation when he was a prisoner of war detailed to remove atomic debris in Japan. Id. at 45-89. Maxwell contends that his claims have failed because of lack of expert assistance in developing the medical and historical facts of his case. As another example, Doris Wilson, a widow who claims her husband's cancer was contracted from exposure to atomic testing, alleges her service representative waived her right to a hearing because he was unprepared to represent her. She contends her claim failed because she was unable, without assistance, to obtain service records and medical information. Id. at 217.

The merits of these claims are difficult to evaluate on the record of affidavits and depositions developed at the preliminary injunction stage. Though the Court concludes that denial of expert representation is not " per se unconstitutional," given the availability of service representatives to assist the veteran and the Veterans' Administration boards' emphasis on nonadversarial procedures,

[o]n remand, the District Court is free to and should consider any individual claims that [the procedures] did not meet the standards we have described in this opinion.

Parham v. J. R., supra, at 442 U. S. 616 -617.