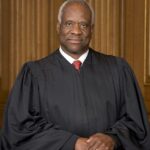

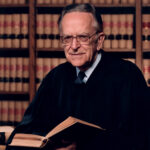

JUSTICE O'CONNOR, with whom THE CHIEF JUSTICE, JUSTICE BLACKMUN, and JUSTICE THOMAS join, dissenting.

In my view, petitioner has not shown by "clear and cogent evidence" that its investment in ASARCO was not operationally related to the aerospace business petitioner conducted in New Jersey. Exxon Corp. v. Department of Reve nue of Wis., 447 U. S. 207, 221 (1980) (internal quotation marks omitted). Though I am largely in agreement with the Court's analysis, I part company on the application of it here.

I agree with the Court that we cannot adopt New Jersey's suggestion that the unitary business principle be replaced by a rule allowing a State to tax a proportionate share of all the income generated by any corporation doing business there. See ante, at 784. Were we to adopt a rule allowing taxation to depend upon corporate identity alone, as New Jersey suggests, the entire due process inquiry would become fictional, as the identities of corporations would fracture in a corporate shell game to avoid taxation. Under New Jersey's theory, for example, petitioner could avoid having its ASARCO investment taxed in New Jersey simply by establishing a separate subsidiary to hold those earnings outside New Jersey. A constitutional principle meant to ensure that States tax only business activities they can reasonably claim to have helped support should depend on something more than manipulations of corporate structure. See Mobil Oil Corp. v. Commissioner of Taxes of Vt., 445 U. S. 425, 440 (1980) ("[T]he form of business organization may have nothing to do with the underlying unity or diversity of business enterprise"); Fargo v. Hart, 193 U. S. 490 (1904) (refusing to find unitary business even though single owner); Adams Express Co. v. Ohio State Auditor, 165 U. S. 194, 222 (1897) (same).

New Jersey suggests that we should presume that all the holdings of a single corporation are mutually interdependent because common ownership will stabilize profits from the commonly held businesses, generating flows of value between them that make them part of a unity. While it may be true that many corporations attempt to diversify their holdings to avoid business cycles, we have refused to presume a flow of value into an in-state business from the potential benefits of being part of a larger multistate, multibusiness corporation. The reason for this is simple: Diversification may benefit the corporation as an entity without necessarily affecting the business activity in the taxing State and without requiring any support from the taxing State. See Wisconsin v. J. C. Penney Co., 311 U. S. 435, 444 (1940) (State may not tax where it has not "given anything for which it can ask return").

I also agree with the Court that there need not be a unitary relationship between the underlying business of a taxpayer and the companies in which it invests in order for a State to tax investment income. See ante, at 787. "[A]ctive operational control" of the investment income payor by the taxpayer is certainly not required. ASARCO Inc. v. Idaho Tax Comm'n, 458 U. S. 307, 343 (1982) (O'CONNOR, J., dissenting). Insofar as a requirement that the investment payor and payee be unitary was suggested by our decisions in ASARCO and F. W Woolworth Co. v. Taxation and Reve nue Dept. of N. M., 458 U. S. 354 (1982), petitioner concedes that was a "doctrinal foot fault." Reply Brief for Petitioner on Reargument 4. Although a unitary relationship between the investment income payor and payee would suffice to relate the investment income to the in-state business, such a connection is not necessary. Taxation of investment income received from a nondomiciliary taxpayer's investment in another corporation requires only that the investment income be sufficiently related to the taxpayer's in-state business, not that the taxpayer's business and the corporation in which it invests be unitary. Only when the State seeks to tax directly the income of a nondomiciliary taxpayer's subsidiary or affiliate through combined reporting, see Container Corp. of America v. Franchise Tax Bd., 463 U. S. 159, 169, and n. 7 (1983), must the underlying businesses of the taxpayer and its affiliate or subsidiary be unitary. In any case, the key question for purposes of due process is whether the income that the State seeks to tax is, by the time it is realized, sufficiently related to a unitary business, part of which operates in the taxing State.

In this connection, I agree with the Court that out-of-state investments serving an operational function in the nondomiciliary taxpayer's in-state business are sufficiently related to that business to be taxed. In particular, I agree that "'interim uses of idle funds "accumulated for the future operation of [the taxpayer's] business [operation],"'" may be taxed. Ante, at 787 (quoting ASARCO, supra, at 325, n. 21). The Court, however, leaves "operational function" largely undefined. I presume that the Court's test allows taxation in at least those circumstances in which it is allowed by the Uniform Division of Income for Tax Purposes Act (UDITPA). Ante, at 786. UDITPA counts as apportionable business income from "tangible and intangible property if the acquisition, management, and disposition of the property constitute integral parts of the taxpayer's regular trade or business operations." UDITPA § l(a), 7A U. L. A. 336 (1985) (emphasis added). Presumably, investment income serves an operational function if it is, to give only some examples, intended to be used by the time it is realized for making the business' anticipated payments; for expanding or replacing plants and equipment; or for acquiring other unitary businesses that will serve the in-state business as stable sources of supply or demand, or that will generate economies of scale or savings in administration.

In its application of these principles to this case, however, I diverge from the Court's analysis. The Court explains that while "interest earned on short-term deposits in a bank located in another State" may be taxed "if that income forms part of the working capital of the corporation's unitary business," petitioner's longer term investment in ASARCO may not be taxed. Ante, at 787. The Court finds the investment here not to be operational because it was not analogous to a "short-term investment of working capital analogous to a bank account or certificate of deposit." Ante, at 790.

Any distinction between short-term and long-term investments cannot be of constitutional dimension. Whether an investment is short-term or long-term, what matters for due process purposes is whether the investment is operationally related to the in-state business. "The interim investment of retained earnings prior to their commitment to a major corporate project… merely recapitulates on a grander scale the short-term investment of working capital prior to its commitment to the daily financial needs of the company." ASARCO, supra, at 338 (O'CONNOR, J., dissenting). I see no distinction relevant to due process between investing in a company in order to build capital to acquire a second company related to the in-state business and, for example, "leas[ing] for a term of years the areas of [the taxpayer's] office buildings into which it intends ultimately to expand," which could hardly be claimed to set up a "separate and unrelated leasing business." 458 U. S., at 338, n. 6. O'CONNOR, J., dissenting

The link between the ASARCa investment here and the in-state business is closer than the Court suggests. It is not just that the ASARCa investment was made to benefit Bendix as a corporate entity. As the Court points out, any investment a corporation makes is intended to benefit the corporation in general. Ante, at 789. The proper question is rather: Was the income New Jersey seeks to tax intended to be used to benefit a unitary business of which Bendix's New Jersey operations were a part?

Petitioner has not carried the heavy burden of showing by clear and cogent evidence that the capital gains from ASARCa were not operationally related to its in-state business. See Container Corp., supra, at 175. Though this case comes to us on a stipulated record, there is no stipulation that the ASARCa capital gains were not intended to be used to benefit a unitary business, part of which operated in New Jersey. Instead, the record suggests that, by the time the capital gains were realized, at least some of the income was intended to be used in the attempt to acquire a corporation also engaged in the aerospace industry. App. 70-71,81, 193. The acquisition of Martin Marietta, had it succeeded, would have been part of petitioner's unitary aerospace business, part of which operated in New Jersey. Id., at 194. As the New Jersey Supreme Court found: "[T]he purpose of acquiring Martin Marietta was to complement the aerospaceelectronics facets of Bendix business, some of which are located in New Jersey…. Even though the Martin Marietta takeover never came to fruition, the fact that it served as a goal for part of the capital generated by the sales of ASARCa… stock nurtures the premise that Bendix's ingrained policy of acquisitions and divestitures projected the existence of a unitary business." Bendix Corp. v. Director, Div. of Taxation, 125 N. J. 20, 38, 592 A. 2d 536, 545 (1991). We will, "if reasonably possible, defer to the judgment of state courts in deciding whether a particular set of activities constitutes a 'unitary business.'" Container Corp., supra, at 175. Because petitioner has failed to show by clear and cogent evidence that the income derived from the ABARCa investment was not related to the operations of its unitary aerospace business, part of which was in New Jersey, New Jersey should be able to apportion and tax that income. As the Court holds that it may not, I must respectfully dissent. The next page is purposely numbered 901. The numbers between 795 and 901 were intentionally omitted, in order to make it possible to publish the orders with permanent page numbers, thus making the official citations available upon publication of the preliminary prints of the United States Reports. MAY 6,1992

Certiorari Denied

No. 91-7832 (A-783). MAY V. COLLINS, DIRECTOR, TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE, INSTITUTIONAL DIVISION. C. A. 5th Cir. Application for stay of execution of sentence of death, presented to JUSTICE SCALIA, and by him referred to the Court, denied. Certiorari denied. Reported below: 955 F.2d 299.

No. 91-8166 (A-823). MAY V. COLLINS, DIRECTOR, TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE, INSTITUTIONAL DIVISION. C. A. 5th Cir. Application for stay of execution of sentence of death, presented to JUSTICE SCALIA, and by him referred to the Court, denied. Certiorari denied. Reported below: 961 F.2d 74.

MAY 7,1992 Dismissal Under Rule 46

No. 91-980. COLORADO ET AL. V. KUHN ET AL. Sup. Ct. Colo.

Certiorari dismissed under this Court's Rule 46. Reported below: 817 P. 2d 101.

Miscellaneous Orders

No. A-824. HILL V. LOCKHART, DIRECTOR, ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION. Application for stay of execution of sentence of death, presented to JUSTICE BLACKMUN, and by him referred to the Court, denied.

No. A-824. HILL V. LOCKHART, DIRECTOR, ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION. Motion to reconsider order of May 7, 1992, denying application for stay of execution denied.

MAY 11, 1992

Miscellaneous Order

No. A-838. MARTIN V. SINGLETARY, SECRETARY, FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS. Application for stay of execution 901

Notes

792 ALLIED-SIGNAL, INC. v. DIRECTOR, DIV. OF TAXATION

794 ALLIED-SIGNAL, INC. v. DIRECTOR, DIV. OF TAXATION