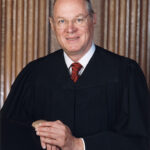

Justice O'CONNOR, with whom The Chief Justice, Justice SCALIA, and Justice KENNEDY join, dissenting.

At the heart of the Constitution's guarantee of equal protection lies the simple command that the Government must treat citizens "as individuals, not as simply components of a racial, religious, sexual or national class.'" Arizona Governing Committee v. Norris, 463 U. S. 1073, 463 U. S. 1083 (1983). Social scientists may debate how peoples' thoughts and behavior reflect their background, but the Constitution provides that the Government may not allocate benefits and burdens among individuals based on the assumption that race or ethnicity determines how they act or think. To uphold the challenged programs, the Court departs from these fundamental principles and from our traditional requirement that racial classifications are permissible only if necessary and narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling interest. This departure marks a renewed toleration of racial classifications and a repudiation of our recent affirmation that the Constitution's equal protection guarantees extend equally to all citizens. The Court's application of a lessened equal protection standard to congressional actions finds no support in our cases or in the Constitution. I respectfully dissent.

I

As we recognized last Term, the Constitution requires that the Court apply a strict standard of scrutiny to evaluate racial classifications such as those contained in the challenged FCC distress sale and comparative licensing policies. See Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U. S. 469 (1989); see also Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954). "Strict scrutiny" requires that, to be upheld, racial classifications must be determined to be necessary and narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling state interest. The Court abandons this traditional safeguard against discrimination for a lower standard of review, and in practice applies a standard like that applicable to routine legislation. Yet the Government's different treatment of citizens according to race is no routine concern. This Court's precedents in no way justify the Court's marked departure from our traditional treatment of race classifications and its conclusion that different equal protection principles apply to these federal actions.

In both the challenged policies, the FCC provides benefits to some members of our society and denies benefits to others based on race or ethnicity. Except in the narrowest of circumstances, the Constitution bars such racial classifications as a denial to particular individuals, of any race or ethnicity, of "the equal protection of the laws." U.S. Const., Amdt. 14, § 1; cf. Croson, supra, at 493-494. The dangers of such classifications are clear. They endorse race-based reasoning and the conception of a Nation divided into racial blocs, thus contributing to an escalation of racial hostility and conflict. See Croson, supra, at 488 U. S. 493 -494. Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 323 U. S. 240 (1944) (Murphy, J., dissenting) (upholding treatment of individual based on inference from race is "to destroy the dignity of the individual and to encourage and open the door to discriminatory actions against other minority groups in the passions of tomorrow"). Such policies may embody stereotypes that treat individuals as the product of their race, evaluating their thoughts and efforts -their very worth as citizens -according to a criterion barred to the Government by history and the Constitution. Accord, Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, 458 U. S. 718, 458 U. S. 725 -726 (1982). Racial classifications, whether providing benefits to or burdening particular racial or ethnic groups, may stigmatize those groups singled out for different treatment and may create considerable tension with the Nation's widely shared commitment to evaluating individuals upon their individual merit. Cf. Regents of University of Calif v. Bakke, 438 U. S. 265, 438 U. S. 358 -362 (1978) (opinion of BRENNAN, J.).

Because racial characteristics so seldom provide a relevant basis for disparate treatment, and because classifications based on race are potentially so harmful to the entire body politic, it is especially important that the reasons for any such classifications be clearly identified and unquestionably legitimate.

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U. S. 448, 448 U. S. 533 -535 (1980) (STEVENS, J., dissenting) (footnotes omitted).

The Constitution's guarantee of equal protection binds the Federal Government as it does the States, and no lower level of scrutiny applies to the Federal Government's use of race classifications. In Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, the companion case to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), the Court held that equal protection principles embedded in the Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause prohibited the Federal Government from maintaining racially segregated schools in the District of Columbia: "[I]t would be unthinkable that the same Constitution would impose a lesser duty on the Federal Government." Id. at 347 U. S. 500. Consistent with this view, the Court has repeatedly indicated that "the reach of the equal protection guarantee of the Fifth Amendment is coextensive with that of the Fourteenth." United States v. Paradise, 480 U. S. 149, 480 U. S. 166, n. 16 (1987) (plurality opinion) (considering remedial race classification); id. at 196 (O'CONNOR, J., dissenting); see also, e.g., Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U. S. 1, 424 U. S. 93 (1976); Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U. S. 636, 420 U. S. 638, n. 2 (1975).

Nor does the congressional role in prolonging the FCC's policies justify any lower level of scrutiny. As with all instances of judicial review of federal legislation, the Court does not lightly set aside the considered judgment of a coordinate branch. Nonetheless, the respect due a coordinate branch yields neither less vigilance in defense of equal protection principles nor any corresponding diminution of the standard of review. In Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, for example, the Court upheld a widower's equal protection challenge to a provision of the Social Security Act, found the assertedly benign congressional purpose to be illegitimate, and noted that

[t]his Court's approach to Fifth Amendment equal protection claims has always been precisely the same as to equal protection claims under the Fourteenth Amendment.

420 U.S. at 420 U. S. 638, n. 2. The Court has not varied its standard of review when entertaining other equal protection challenges to congressional measures. See, e.g., Heckler v. Mathews, 465 U. S. 728 (1984); Califano v. Webster, 430 U. S. 313 (1977) (per curiam ); Califano v. Goldfarb, 430 U. S. 199, 430 U. S. 210 -211 (1977) (traditional equal protection standard applies despite deference to congressional benefit determinations) (opinion of BRENNAN, J.); Buckley v. Valeo, supra, at 424 U. S. 93 ; Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U. S. 677, 411 U. S. 684 -691 (1973) (opinion of BRENNAN, J.). And Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, itself involved extensive congressional regulation of the segregated District of Columbia public schools.

Congress has considerable latitude, presenting special concerns for judicial review, when it exercises its "unique remedial powers… under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment," see Croson, supra, at 488 U. S. 488 (opinion of O'CONNOR, J.), but this case does not implicate those powers. Section 5 empowers Congress to act respecting the States, and of course this case concerns only the administration of federal programs by federal officials. Section 5 provides to Congress the "power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article," which in part provides that "[n]o State shall… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." U.S. Const.Amdt. 14, § 1. Reflecting the Fourteenth Amendment's "dramatic change in the balance between congressional and state power over matters of race," Croson, 488 U.S. at 488 U. S. 490 (opinion of O'CONNOR, J.), that section provides to Congress a particular structural role in the oversight of certain of the States' actions. See id. at 488 U. S. 488 -491, 504; Hogan, supra, at 458 U. S. 732 (§ 5 grants power to enforce Amendment " to secure equal protection of the laws against State denial or invasion,'" quoting Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 100 U. S. 346 (1880)); Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 476 -478, 448 U. S. 483 -484.

The Court asserts that Fullilove supports its novel application of intermediate scrutiny to "benign" race-conscious measures adopted by Congress. Ante at 497 U. S. 564. Three reasons defeat this claim. First, Fullilove concerned an exercise of Congress' powers under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Fullilove, the Court reviewed an act of Congress that had required States to set aside a percentage of federal construction funds for certain minority-owned businesses to remedy past discrimination in the award of construction contracts. Although the various opinions in Fullilove referred to several sources of congressional authority, the opinions make clear that it was § 5 that led the Court to apply a different form of review to the challenged program. See, e.g., 448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 483 ("[I]n no organ of government, state or federal, does there repose a more comprehensive remedial power than in the Congress, expressly charged by the Constitution with competence and authority to enforce equal protection guarantees") (opinion of Burger, C.J., joined by WHITE, J., and Powell, J.); id. at 448 U. S. 508 -510, 516 (Powell, J., concurring). Last Term, Croson resolved any doubt that might remain regarding this point. In Croson, we invalidated a local set-aside for minority contractors. We distinguished Fullilove, in which we upheld a similar set-aside enacted by Congress, on the ground that, in Fullilove "Congress was exercising its powers under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment." Croson, 488 U.S. at 488 U. S. 504 (opinion of the Court); id. at 488 U. S. 490 (opinion of O'CONNOR, J., joined by REHNQUIST, C.J., and WHITE, J.). Croson indicated that the decision in Fullilove turned on "the unique remedial powers of Congress under § 5," id. at 488 U. S. 488 (opinion of O'CONNOR, J.), and that the latitude afforded Congress in identifying and redressing past discrimination rested on § 5's "specific constitutional mandate to enforce the dictates of the Fourteenth Amendment." Id. at 488 U. S. 490. Justice KENNEDY's concurrence in Croson likewise provides the majority with no support, for it questioned whether the Court should, as it had in Fullilove, afford any particular latitude even to measures undertaken pursuant to § 5. See id., 488 U.S. at 488 U. S. 518.

Second, Fullilove applies at most only to congressional measures that seek to remedy identified past discrimination. The Court upheld the challenged measures in Fullilove only because Congress had identified discrimination that had particularly affected the construction industry, and had carefully constructed corresponding remedial measures. See Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 488 U. S. 456 -467, 488 U. S. 480 -489 (opinion of Burger, C.J.); id. at 488 U. S. 498 -499 (opinion of Powell, J.). Fullilove indicated that careful review was essential to ensure that Congress acted solely for remedial, rather than other, illegitimate purposes. See id. at 488 U. S. 486 -487 (opinion of Burger, C.J.); id. at 488 U. S. 498 -499 (opinion of Powell, J.). The FCC and Congress are clearly not acting for any remedial purpose, see infra at 497 U. S. 611 -612, and the Court today expressly extends its standard to racial classifications that are not remedial in any sense. See ante at 497 U. S. 564 -565. This case does not present "a considered decision of the Congress and the President," Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 473 ; see infra at 497 U. S. 628 -629, nor does it present a remedial effort or exercise of § 5 powers.

Finally, even if Fullilove applied outside a remedial exercise of Congress' § 5 power, it would not support today's adoption of the intermediate standard of review proffered by Justice MARSHALL but rejected in Fullilove. Under his suggested standard, the Government's use of racial classifications need only be " substantially related to achievement'" of important governmental interests. Ante at 497 U. S. 565. Although the Court correctly observes that a majority did not apply strict scrutiny, six Members of the Court rejected intermediate scrutiny in favor of some more stringent form of review. Three Members of the Court applied strict scrutiny. See 448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 496 (Powell, J., concurring) (challenged statute "employs a racial classification that is constitutionally prohibited unless it is necessary means of advancing a compelling governmental interest"); id. at 448 U. S. 498 ("means selected must be narrowly drawn"). Id. at 448 U. S. 523 (Stewart, J., joined by REHNQUIST, J. dissenting). Chief Justice Burger's opinion, joined by Justice WHITE and Justice Powell, declined to adopt a particular standard of review, but indicated that the Court must conduct "a most searching examination," Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 491, and that courts must ensure that

any congressional program that employs racial or ethnic criteria to accomplish the objective of remedying the present effects of past discrimination is narrowly tailored to the achievement of that goal.

Id. at 448 U. S. 480. Justice STEVENS indicated that "[r]acial classifications are simply too pernicious to permit any but the most exact connection between justification and classification." Id. at 448 U. S. 537 (STEVENS, J., dissenting). Even Justice MARSHALL's opinion, joined by Justice BRENNAN and Justice BLACKMUN, undermines the Court's course today: that opinion expressly drew its lower standard of review from the plurality opinion in Regents of University of Calif. v. Bakke, 438 U. S. 265 (1978), a case that did not involve congressional action, and stated that the appropriate standard of review for the congressional measure challenged in Fullilove "is the same as that under the Fourteenth Amendment." 448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 517 -518, n. 2 (internal quotation omitted). And, of course, Fullilove preceded our determination in Croson that strict scrutiny applies to preferences that favor members of minority groups, including challenges considered under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The guarantee of equal protection extends to each citizen, regardless of race: the Federal Government, like the States, may not "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." As we observed only last Term in Croson,

[a]bsent searching judicial inquiry into the justification for such race-based measures, there is simply no way of determining what classifications are 'benign' or 'remedial' and what classifications are in fact motivated by illegitimate notions of racial inferiority or simple racial politics.

Croson, 488 U.S. at 488 U. S. 493 ; see also id. at 488 U. S. 494 ("the standard of review under the Equal Protection Clause is not dependent on the race of those burdened or benefited by a particular classification").

The Court's reliance on "benign racial classifications," ante at 497 U. S. 564, is particularly troubling. " Benign' racial classification" is a contradiction in terms. Governmental distinctions among citizens based on race or ethnicity, even in the rare circumstances permitted by our cases, exact costs and carry with them substantial dangers. To the person denied an opportunity or right based on race, the classification is hardly benign. The right to equal protection of the laws is a personal right, see Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 334 U. S. 22 (1948), securing to each individual an immunity from treatment predicated simply on membership in a particular racial or ethnic group. The Court's emphasis on "benign racial classifications" suggests confidence in its ability to distinguish good from harmful governmental uses of racial criteria. History should teach greater humility. Untethered to narrowly confined remedial notions, "benign" carries with it no independent meaning, but reflects only acceptance of the current generation's conclusion that a politically acceptable burden, imposed on particular citizens on the basis of race, is reasonable. The Court provides no basis for determining when a racial classification fails to be "benevolent." By expressly distinguishing "benign" from remedial race-conscious measures, the Court leaves the distinct possibility that any racial measure found to be substantially related to an important governmental objective is also, by definition, "benign." See ante at 497 U. S. 564 -565. Depending on the preference of the moment, those racial distinctions might be directed expressly or in practice at any racial or ethnic group. We are a Nation not of black and white alone, but one teeming with divergent communities knitted together by various traditions and carried forth, above all, by individuals. Upon that basis, we are governed by one Constitution, providing a single guarantee of equal protection, one that extends equally to all citizens.

This dispute regarding the appropriate standard of review may strike some as a lawyers' quibble over words, but it is not. The standard of review establishes whether and when the Court and Constitution allow the Government to employ racial classifications. A lower standard signals that the Government may resort to racial distinctions more readily. The Court's departure from our cases is disturbing enough, but more disturbing still is the renewed toleration of racial classifications that its new standard of review embodies.

II

Our history reveals that the most blatant forms of discrimination have been visited upon some members of the racial and ethnic groups identified in the challenged programs. Many have lacked the opportunity to share in the Nation's wealth and to participate in its commercial enterprises. It is undisputed that minority participation in the broadcasting industry falls markedly below the demographic representation of those groups, see, e.g., Congressional Research Service, Minority Broadcast Station Ownership and Broadcast Programming: Is There a Nexus? 42 (June 29, 1988) (minority owners possess an interest in 13.3 percent of stations and a controlling interest in 3.5 percent of stations), and this shortfall may be traced in part to the discrimination and the patterns of exclusion that have widely affected our society. As a Nation, we aspire to create a society untouched by that history of exclusion, and to ensure that equality defines all citizens' daily experience and opportunities, as well as the protection afforded to them under law.

For these reasons, and despite the harms that may attend the Government's use of racial classifications, we have repeatedly recognized that the Government possesses a compelling interest in remedying the effects of identified race discrimination. We subject even racial classifications claimed to be remedial to strict scrutiny, however, to ensure that the Government in fact employs any race-conscious measures to further this remedial interest, and employs them only when, and no more broadly than, the interest demands. See, e.g., Croson, 488 U.S. at 488 U. S. 493 -495, 488 U. S. 498 -502; Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Ed., 476 U. S. 267 (1986) (plurality opinion). The FCC or Congress may yet conclude, after suitable examination, that narrowly tailored race-conscious measures are required to remedy discrimination that may be identified in the allocation of broadcasting licenses. Such measures are clearly within the Government's power.

Yet it is equally clear that the policies challenged in these cases were not designed as remedial measures, and are in no sense narrowly tailored to remedy identified discrimination. The FCC appropriately concedes that its policies embodied no remedial purpose, Tr. of Oral Arg. 40-42, and has disclaimed the possibility that discrimination infected the allocation of licenses. The congressional action, at most, simply endorsed a policy designed to further the interest in achieving diverse programming. Even if the appropriations measure could transform the purpose of the challenged policies, its text reveals no remedial purpose, and the accompanying legislative material confirms that Congress acted upon the same diversity rationale that led the FCC to formulate the challenged policies. See S.Rep. No. 100-182, p. 76 (1987). The Court refers to the bare suggestion, contained in a report addressing different legislation passed in 1982, that "past inequities" have led to

underrepresentation of minorities in the media of mass communications, as it has adversely affected their participation in other sectors of the economy as well.

H.R.Conf.Rep. No. 97-765, p. 43 (1982), U.S.Code Cong. & Admin.News 1982, 2287; ante at 497 U. S. 566. This statement indicates nothing whatever about the purpose of the relevant appropriations measures, identifies no discrimination in the broadcasting industry, and would not sufficiently identify discrimination even if Congress were acting pursuant to its § 5 powers. Cf. Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 456 -467 (opinion of Burger, C.J.) (surveying identification of discrimination affecting contracting opportunities); id. at 448 U. S. 502 -506 (Powell, J., concurring). The Court evaluates the policies only as measures designed to increase programming diversity. Ante at 497 U. S. 566 -568. I agree that the racial classifications cannot be upheld as remedial measures.

III

Under the appropriate standard, strict scrutiny, only a compelling interest may support the Government's use of racial classifications. Modern equal protection doctrine has recognized only one such interest: remedying the effects of racial discrimination. The interest in increasing the diversity of broadcast viewpoints is clearly not a compelling interest. It is simply too amorphous, too insubstantial, and too unrelated to any legitimate basis for employing racial classifications. The Court does not claim otherwise. Rather, it employs its novel standard and claims that this asserted interest need only be, and is, "important." This conclusion twice compounds the Court's initial error of reducing its level of scrutiny of a racial classification. First, it too casually extends the justifications that might support racial classifications, beyond that of remedying past discrimination. We have recognized that racial classifications are so harmful that

[u]nless they are strictly reserved for remedial settings, they may in fact promote notions of racial inferiority and lead to a politics of racial hostility.

Croson, supra, at 488 U. S. 493. As Chief Justice Burger warned in Fullilove,

The history of governmental tolerance of practices using racial or ethnic criteria for the purpose or with the effect of imposing an invidious discrimination must alert us to the deleterious effects of even benign racial or ethnic classifications when they stray from narrow remedial justifications.

448 U.S. at 448 U. S. 486 -487. Second, it has initiated this departure by endorsing an insubstantial interest, one that is certainly insufficiently weighty to justify tolerance of the Government's distinctions among citizens based on race and ethnicity. This endorsement trivializes the constitutional command to guard against such discrimination and has loosed a potentially far-reaching principle disturbingly at odds with our traditional equal protection doctrine.

An interest capable of justifying race-conscious measures must be sufficiently specific and verifiable, such that it supports only limited and carefully defined uses of racial classifications. In Croson, we held that an interest in remedying societal discrimination cannot be considered compelling. See 488 U.S. at 488 U. S. 505 (because the City of Richmond had presented no evidence of identified discrimination, it had "failed to demonstrate a compelling interest in apportioning public contracting opportunities on the basis of race"). We determined that a "generalized assertion" of past discrimination "has no logical stopping point" and would support unconstrained uses of race classifications. See id. at 488 U. S. 498 (internal quotation omitted). In Wygant, we rejected the asserted interest in "providing minority role models for [a public school system's] minority students, as an attempt to alleviate the effects of societal discrimination," 476 U.S. at 476 U. S. 274 (plurality opinion), because "[s]ocietal discrimination, without more, is too amorphous a basis for imposing a racially classified remedy" and would allow "remedies that are ageless in their reach into the past, and timeless in their ability to affect the future." Id. at 476 U. S. 276. Both cases condemned those interests because they would allow distribution of goods essentially according to the demographic representation of particular racial and ethnic groups. See Croson, 488 U.S. at 488 U. S. 498, 488 U. S. 505 -506, 488 U. S. 507 ; Wygant, 476 U.S. at 476 U. S. 276 (plurality opinion).

The asserted interest in this case suffers from the same defects. The interest is certainly amorphous: the FCC and the majority of this Court understandably do not suggest how one would define or measure a particular viewpoint that might be associated with race, or even how one would assess the diversity of broadcast viewpoints. Like the vague assertion of societal discrimination, a claim of insufficiently diverse broadcasting viewpoints might be used to justify equally unconstrained racial preferences, linked to nothing other than proportional representation of various races. And the interest would support indefinite use of racial classifications, employed first to obtain the appropriate mixture of racial views and then to ensure that the broadcasting spectrum continues to reflect that mixture. We cannot deem to be constitutionally adequate an interest that would support measures that amount to the core constitutional violation of "outright racial balancing." Croson, supra, at 488 U. S. 507.

The asserted interest would justify discrimination against members of any group found to contribute to an insufficiently diverse broadcasting spectrum, including those groups currently favored. In Wygant, we rejected as insufficiently weighty the interest in achieving role models in public schools, in part because that rationale could as readily be used to limit the hiring of teachers who belonged to particular minority groups. See Wygant, supra, at 476 U. S. 275 -276 (plurality opinion). The FCC's claimed interest could similarly justify limitations on minority members' participation in broadcasting. It would be unwise to depend upon the Court's restriction of its holding to "benign" measures to forestall this result. Divorced from any remedial purpose and otherwise undefined, "benign" means only what shifting fashions and changing politics deem acceptable. Members of any racial or ethnic group, whether now preferred under the FCC's policies or not, may find themselves politically out of fashion and subject to disadvantageous but "benign" discrimination.

Under the majority's holding, the FCC may also advance its asserted interest in viewpoint diversity by identifying what constitutes a "Black viewpoint," an "Asian viewpoint," an "Arab viewpoint," and so on; determining which viewpoints are underrepresented; and then using that determination to mandate particular programming or to deny licenses to those deemed by virtue of their race or ethnicity less likely to present the favored views. Indeed, the FCC has, if taken at its word, essentially pursued this course, albeit without making express its reasons for choosing to favor particular groups or for concluding that the broadcasting spectrum is insufficiently diverse. See Statement of Policy on Minority Ownership of Broadcasting Facilities, 68 F.C.C.2d 979 (1978) ( 1978 Policy Statement ).

We should not accept as adequate for equal protection purposes an interest unrelated to race, yet capable of supporting measures so difficult to distinguish from proscribed discrimination. The remedial interest may support race classifications because that interest is necessarily related to past racial discrimination; yet the interest in diversity of viewpoints provides no legitimate, much less important, reason to employ race classifications apart from generalizations impermissibly equating race with thoughts and behavior. And it will prove impossible to distinguish naked preferences for members of particular races from preferences for members of particular races because they possess certain valued views: no matter what its purpose, the Government will be able to claim that it has favored certain persons for their ability, stemming from race, to contribute distinctive views or perspectives.

Even considered as other than a justification for using race classifications, the asserted interest in viewpoint diversity falls short of being weighty enough. The Court has recognized an interest in obtaining diverse broadcasting viewpoints as a legitimate basis for the FCC, acting pursuant to its "public interest" statutory mandate, to adopt limited measures to increase the number of competing licensees and to encourage licensees to present varied views on issues of public concern. See, e.g., FCC v. National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting, 436 U. S. 775 (1978); Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U. S. 367 (1969); United States v. Storer Broadcasting Co., 351 U. S. 192 (1956); Associated Press v. United States, 326 U. S. 1 (1945); National Broadcasting Co. v. United States, 319 U. S. 190 (1943). We have also concluded that these measures do not run afoul of the First Amendment's usual prohibition of Government regulation of the marketplace of ideas, in part because First Amendment concerns support limited but inevitable Government regulation of the peculiarly constrained broadcasting spectrum. See, e.g., Red Lion, supra, at 395 U. S. 389 -390. But the conclusion that measures adopted to further the interest in diversity of broadcasting viewpoints are neither beyond the FCC's statutory authority nor contrary to the First Amendment hardly establishes the interest as important for equal protection purposes.

The FCC's extension of the asserted interest in diversity of views in this case presents, at the very least, an unsettled First Amendment issue. The FCC has concluded that the American broadcasting public receives the incorrect mix of ideas and claims to have adopted the challenged policies to supplement programming content with a particular set of views. Although we have approved limited measures designed to increase information and views generally, the Court has never upheld a broadcasting measure designed to amplify a distinct set of views or the views of a particular class of speakers. Indeed, the Court has suggested that